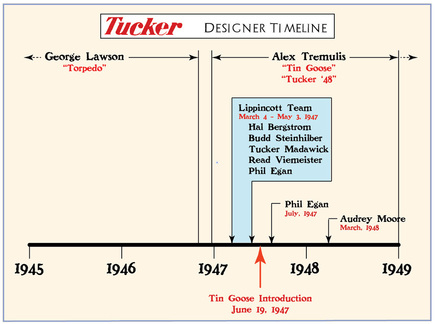

On March 11 the Lippincott team arrived at the Tucker plant, led by Hal Bergstrom and accompanied by additional designers Budd Steinhilber, Tucker Madawick, Read Viemeister and Phil Egan. Here's how Phil Egan described Alex Tremulis' plant tour and his reaction to seeing the "Tin Goose" for the first time:

“Here we saw embryonic shapes in raw sheet metal coalescing into the frame and part of the body of an automobile. A nearby drop hammer pounded sheet metal from flat to contoured with ear-splitting vibrations, and the junctions of formed sheet and frame were fused under the bright sparks of welding torches. Elsewhere, men at work stations devoted themselves to the mechanical details of torching, cutting, bending, and drilling the parts of a prototype automobile. Alex [Tremulis} gave us a cursory introduction to all of this and then led us to the design area.

Since he had accepted the position of chief stylist in January, Alex had brought the design of the Tucker automobile from the nebulous to the three-dimensional. He had developed a firm layout of the car which he showed us in a 1/8 size drawing, with every outside and inside dimension carefully indicated.”

So, even though Alex Tremulis had said to Phil Egan that he felt the Tin Goose's body was 95% complete before the Lippincott arrival, it's probable he meant that it was 95% complete towards the design as it stood at that time. It's also entirely possible that it was also 95% complete during its refinement period while the Lippincott team was in-house, even through all its layers of modifications, right up until its introduction. Much like shoveling snow off a driveway in a snowstorm, it never really is finished.

After the Lippincott team's styling contributions were completed on May 3, and before the Tin Goose introduction on June 19, Egan further clarified Tremulis' role: "Alex Tremulis was primarily responsible for guiding the fabrication of the Tin Goose to conclusion. He was privy to Preston Tucker's decisions regarding those portions of the no. 1 and no. 2 clay models that would be shown to the public. The logistics were mind-boggling. Alex had to coordinate his collegues in sheet metal forming, body engineering, engine and drivetrain design, interior furnishings, instrumentation/controls and painting to produce the final product to the satisfaction of the boss. It had to be beautiful, it had to be convincing and it had to run." - Phil Egan, Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile, 1989

J. Gordon Lippincott had stated that once the clay models were completed (May 3, 1947) it was left to Tucker and Tremulis to assemble the prototype and the cars themselves. Lippincott's involvement was over. Phil Egan and J. Gordon Lippincott both were in agreement that "Tremulis deserves most of the credit for the car design, but that the front and back of the car reflect the Lippincott team's work." Lippincott continued, "it's hard to pinpoint responsibility when many designers have a hand in a project."

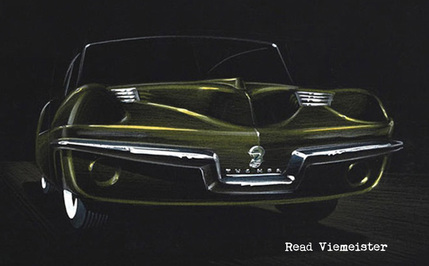

In any case, It's very clear that the Tucker '48 represents the best design elements from each of the designers that contributed to its creation, and each of them, George Lawson, Alex Tremulis, Budd Steinhilber, Hal Bergstrom, Read Viemeister, Tucker Madawick, Phil Egan and Audrey Moore got it right when the final design rolled out of the Tucker manufacturing plant. The car would not have been the same without any one of their design inputs and should be celebrated as such.

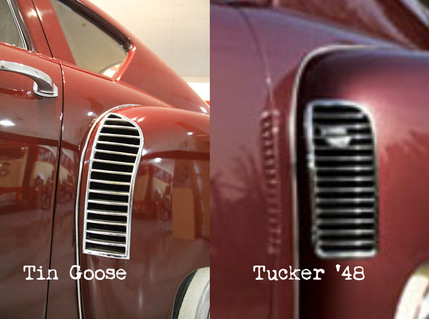

So here's a look at the individual design elements that made the Tin Goose and their evolution from initial design to the Tin Goose to the production Tucker '48s...

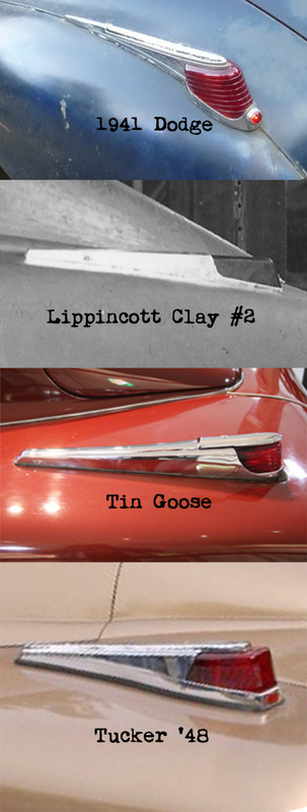

Tremulis' sense of humor and possible shared frustration with slow progress may have been taken out of context by the author, Charles Pearson, as it has already been pointed out that the Lippincott team provided significant input towards the final design of the Tucker '48, however Tremulis was probably accurate about the cost of the taillights. The Tin Goose's taillights are the only two castings (possibly machined?) in existence, and vendors were known to overcharge Tucker for products and services.

But neither the taillights on the Tin Goose nor on any of the Tucker '48's appear to be off-the-shelf Dodge lights, so perhaps custom (and expensive) castings were made for both the Tin Goose and the subsequent cars.

May 4, 1947: The taillights on Clay #2 were modernized versions of the Dodge taillights, with a sleeker profile, squared-off edges, and a much cleaner look.

June 18, 1947: These unique Tin Goose taillights reverted back to the 1941 Dodge design, with a more rounded look and a heavy chrome cap to hold the lens in place, but they don't appear to be from Dodge. These are the only two known taillights of this design, so Tremulis' comments as to their cost may have been right on target.

Tucker '48: The final taillight design was similar to the sleek Lippincott design on Clay #2, with the leading edge lens angle reversed, combined with the top cap similar to the 1941 Dodge.

Even then, though, it wasn't over. The first 25 cars had one casting and due to a rear fender shape change, the last 25 cars were finished with a different contour to the casting. So, yes, the Tucker tail lights were probably the most expensive in automotive history!

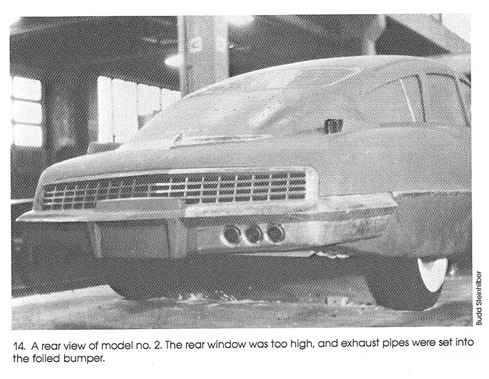

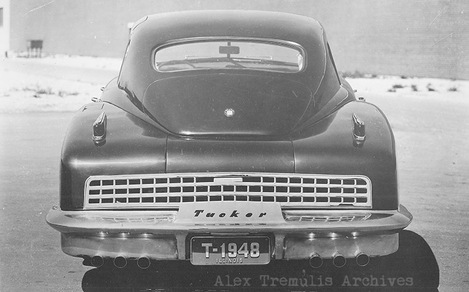

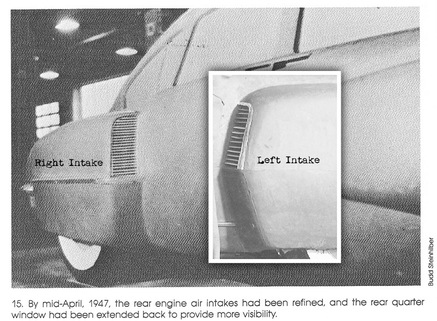

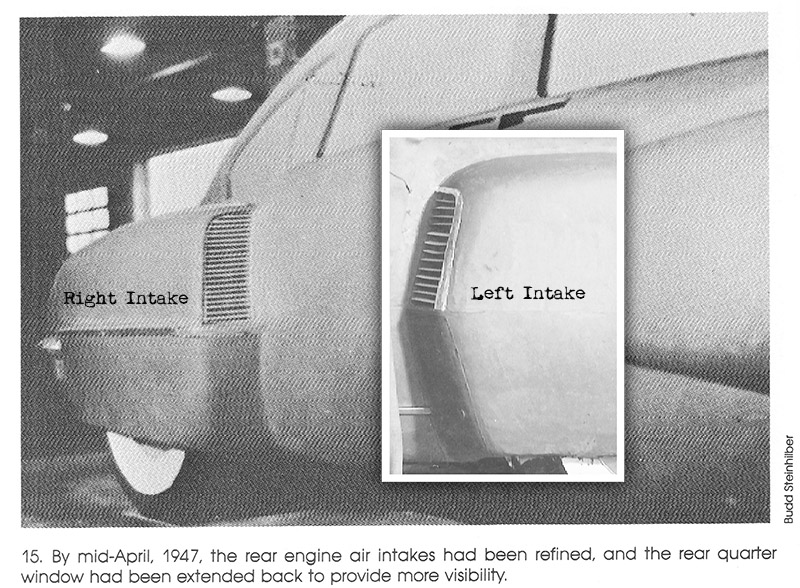

REAR AIR INTAKE

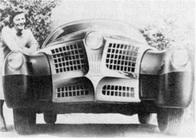

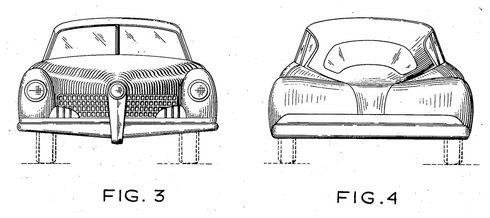

FRONT GRILLE AND BUMPER

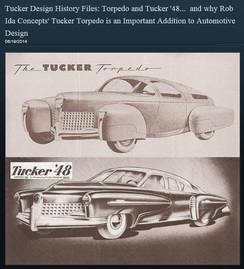

OVERALL SILHOUETTE

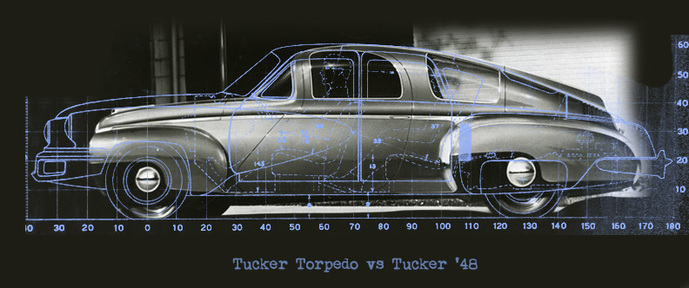

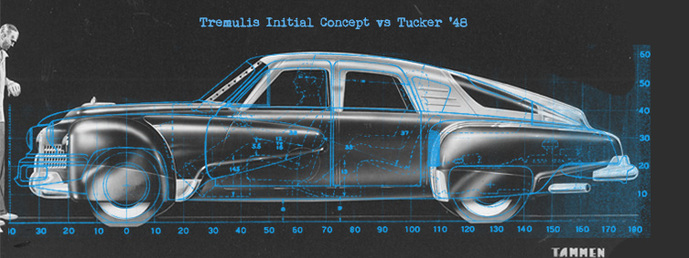

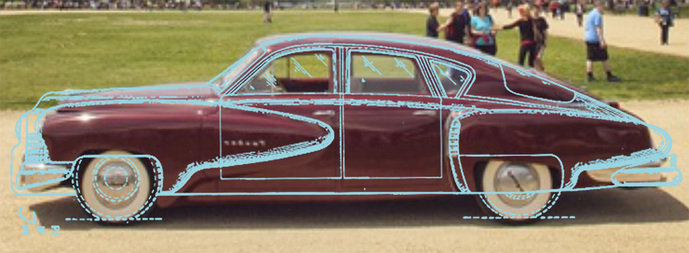

So, Charles Pearson's account for their work in December 1946 appears to be an accurate account, at least for the cabin: "The dimensions set up at this time were, with few exceptions, the ones that were used in the final body design. There was no great attempt at styling, though the side silhouette was nearly identical with the finished design. An extra four inches were allowed on wheelbase, because Tucker was still insisting on fenders that turned with the wheels, and the production man said there would be plenty of time to talk him out of that later." - Charles Pearson, The Indomitable Tin Goose, 1960

As a quick check, comparing Tremulis' very first renderings for Preston Tucker in December 1946 to the final tooling dimensions as of September 1947, the dimensions remained little changed throughout all the development of the Tin Goose and the production Tuckers, confirming Pearson's accounting of events. It also serves to highlight Tremulis' innate ability to pull off some remarkable styling, moveable fenders or fixed, while remaining within the confines of fixed dimensions. A closer look reveals that the doors, window locations, and fender contours for the final design were changed very little from his initial reactions to the car, further suggesting that those dimensions were frozen.

It appears that a new full-sized drawing is being prepared of the flowing fendered design that became the Tin Goose. This also would explain why there were several layers of metal on the Tin Goose, where they had changed from the initial drawings to the fixed fender design, to the small sheet metal changes provided by the two full-sized clay models during the Lippincott team's residency. It's clear the metal body of the Tin Goose was evolving from the beginning and constantly changing throughout the first half of 1947, up until its introduction in June of 1947.

REAR FENDERS and SIDE WINDOWS

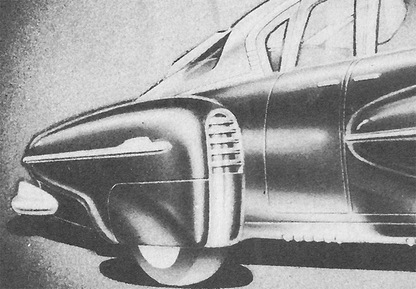

FRONT FENDERS

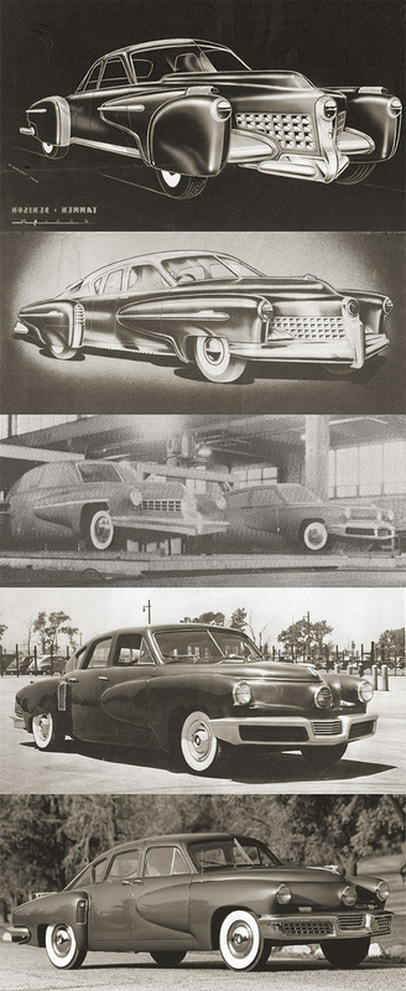

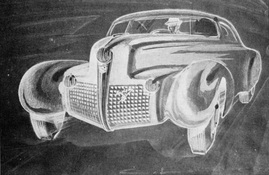

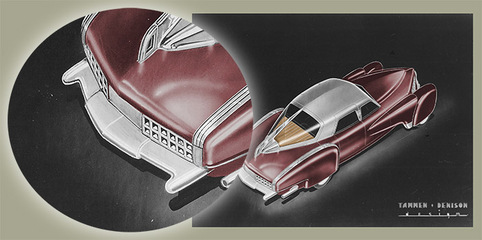

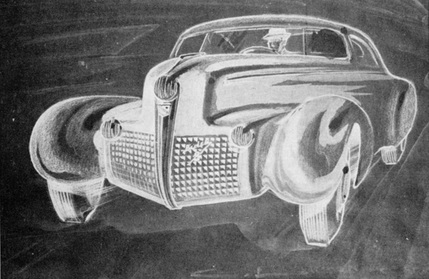

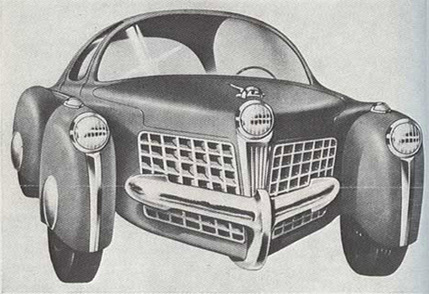

January 1947: Alex Tremulis' first series with the moveable front fenders.

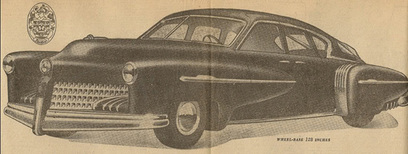

February 1947: The fixed-fender design as used for advertising.

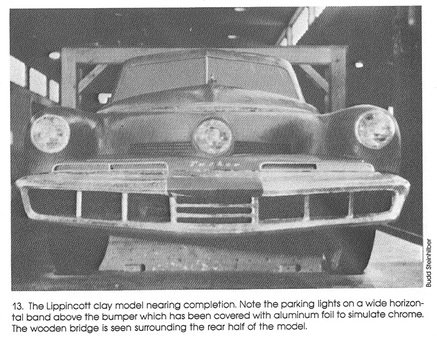

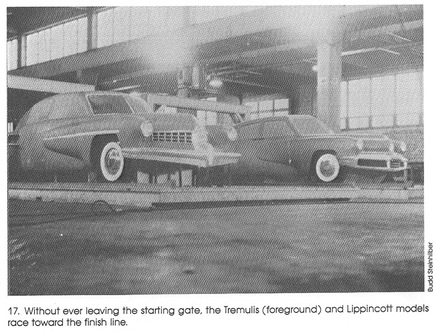

April 1947: Tremulis' Clay #1 in the foreground and the right side of Lippincott's Clay #2 both carry Tremulis' sweeping pontoons.

June 1947: The Tin Goose, now with all the side chrome eliminated.

March 1948: The Tucker '48 again with the pontoons closely mimicking Tremulis' contours of February 1947, just slightly more pointed than those on the Tin Goose.

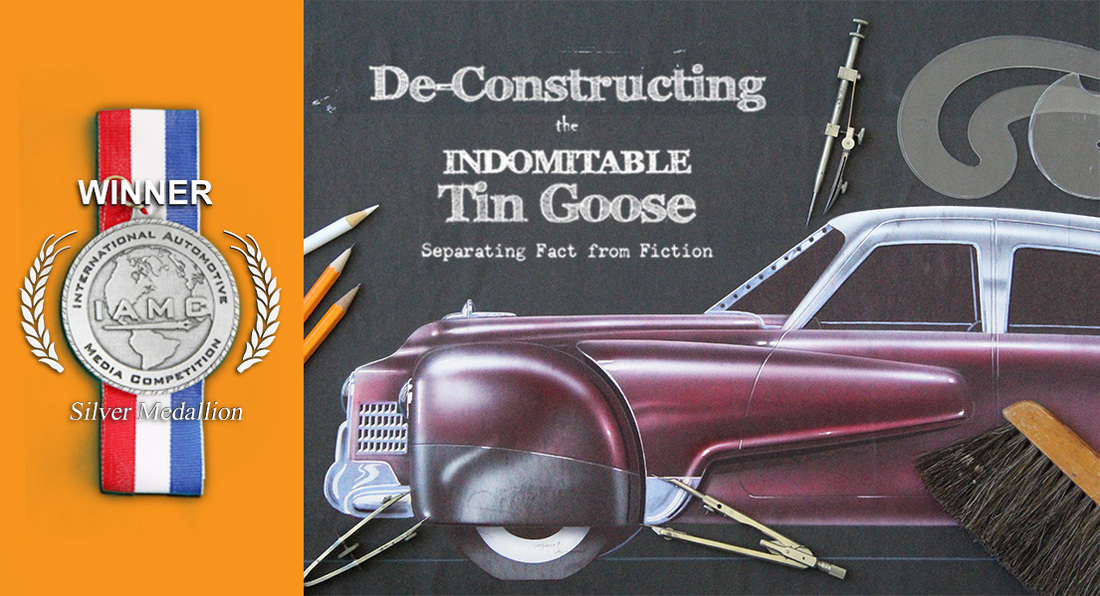

| To learn more about Alex Tremulis' involvement with Preston Tucker and the iconic Tucker automobile, just click the photo at left for Part 1... Published in 1960, The Indomitable Tin Goose provides an insider's accounting for the events during much of the building of Tucker's "Car of Tomorrow". The author, Charles Pearson, was Preston Tucker's public relations manager from mid-1946 until the end of 1947. This would be the most active and productive timeframe for the design efforts to build the Tucker '48. The details of Tucker's travails in obtaining the facilities and financing are particularly interesting. Written so that it's readable, despite containing so much historical information that could have been lifeless. |

| Published in 1989 at the height of the popularity of the Francis Ford Coppola movie, Tucker: A Man and His Dream. The author, Phil Egan, was a member of the Lippincott design team that spent two months at Tucker prior to the unveiling of the Tin Goose prototype. Alex Tremulis would later hire Egan directly to help with the many design details that would be needed to produce the 50 Tucker '48's that represent the entire production output from the factory. Many of the great photographs from inside the Tucker walls were provided by Lippincott designer Budd Steinhilber, to document the progress made on the clay models used for styling ideas. |

| A must watch. Very entertaining and fast paced account of the rise and fall of the Tucker Corporation. Nominated for three Academy Awards in Best Supporting Actor (Martin Landau), Best Art Direction (Dean Tavoularis), and Best Costume Design (Milena Canonero), Landau would take home the Oscar. Alex Tremulis was portrayed by actor Elias Koteas, a near-perfect look-alike, for the automobile design veteran. Although fictionalized, it provides a great backdrop to learn more about the Tucker cars and the people that produced them. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed