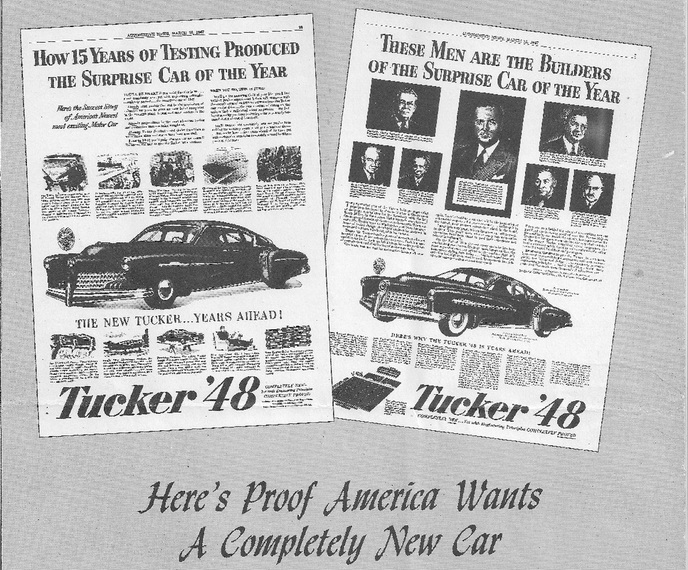

Over the past few decades, an entire new generation of automobile enthusiasts have been introduced to Preston Tucker's "Car of Tomorrow", yet many rely upon rumors and innuendo as to why and how the company failed. The controversy continues as no "smoking gun" has yet been found that definitively points to the US Government conspiring with the "Big Three" to put Preston Tucker out of business for creating a car that was too good.

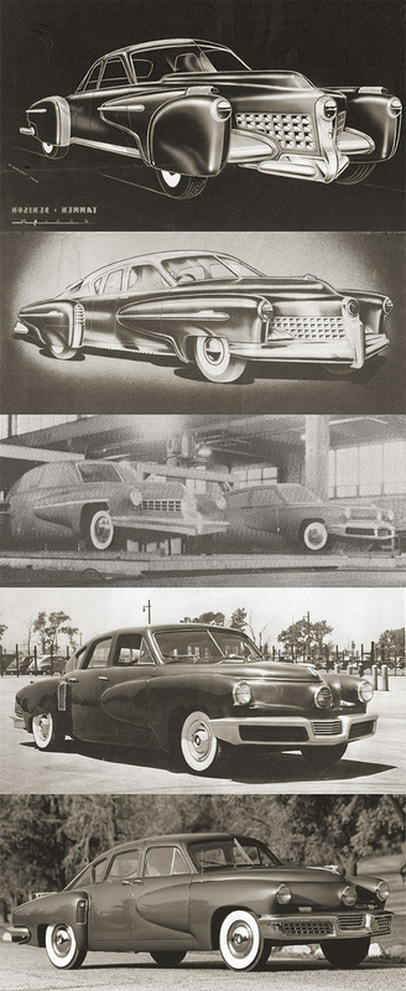

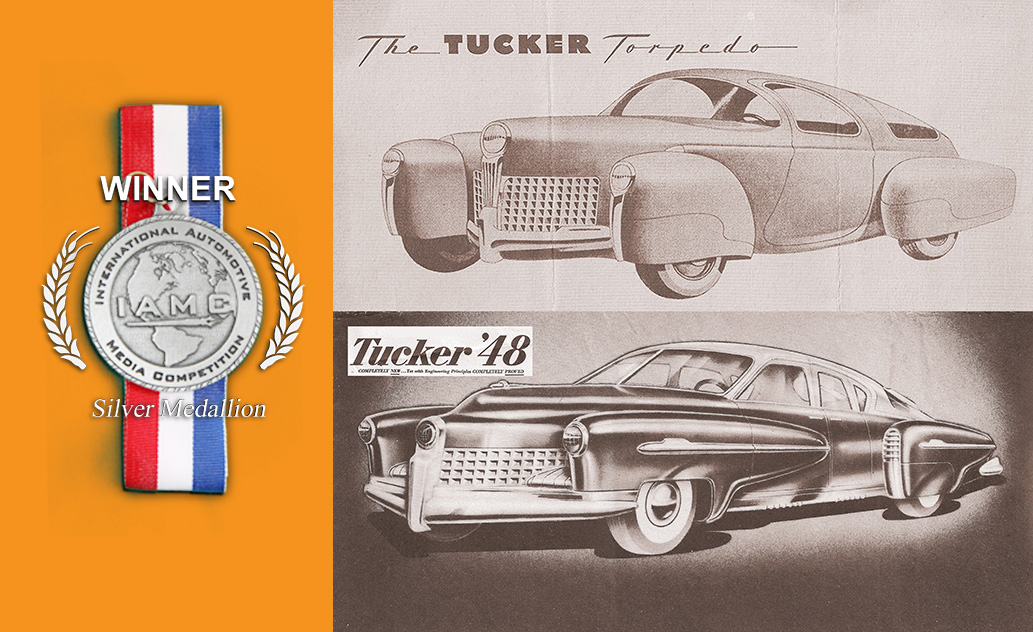

So although there is room for various opinions on the demise of the corporation, the facts surrounding the design for the car are a bit less controversial, yet no less fascinating. So here's a look at the evolution of the Tucker Tin Goose prototype and how each of its design elements evolved into the car that is instantly recognizable as the Tucker '48.

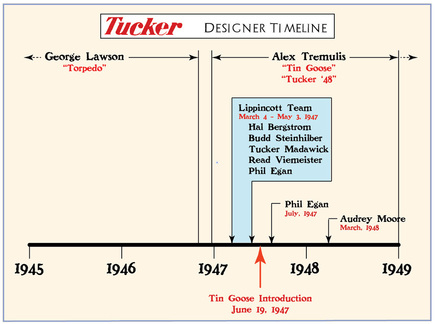

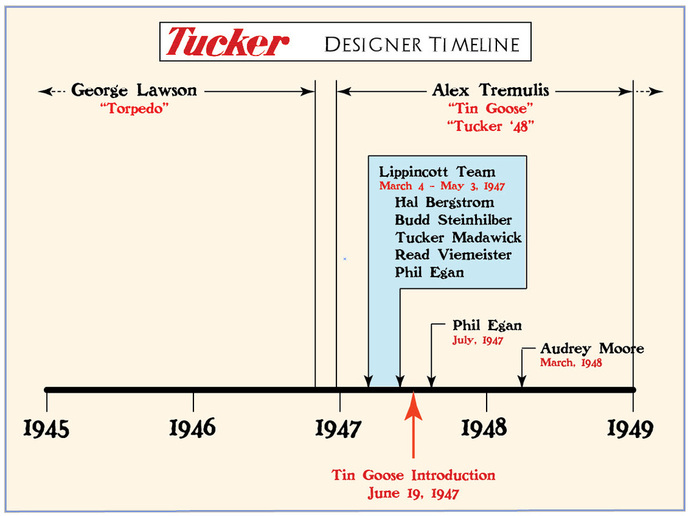

DESIGNER TIMELINE

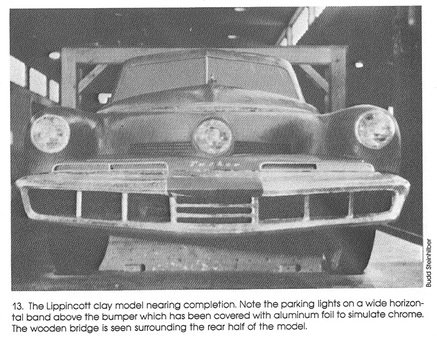

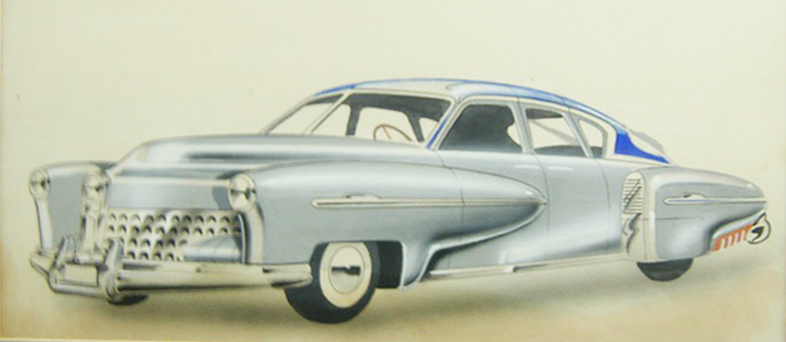

The transformation from Tremulis' layout into the Tin Goose with no clay (direct to metal) had started in January 1947 and was well-underway, if not nearly complete by April, as far as the body's sheet metal was concerned. Phil Egan, a designer on the Lippincott team, recalled their first discussions with Preston Tucker: "Preston Tucker gave us this charge: to style the car based upon the essentials of his mechanical concepts and upon Alex Tremulis' body layout. At no point in the meeting was there any mention of our changing the fundamentals of wheelbase, wheel tread, interior dimensions or even basic body shape. It was a classic case of pure styling. The primary dimensions were inviolate, as were the the tapering roof, and of course, the Cyclops eye front and center (we were to have fun with that feature). Outside of these requirements, there were no constraints. We were expected to go all out in our efforts."

The following paragraphs were discussed in Part 1 (click HERE to learn more about how the Torpedo design morphed into the Tucker '48), but it's worth repeating as it is relevant to the analysis of the design changes that went into building the Tin Goose:

On March 11 the Lippincott team arrived at the Tucker plant, led by Hal Bergstrom and accompanied by additional designers Budd Steinhilber, Tucker Madawick, Read Viemeister and Phil Egan. Here's how Phil Egan described Alex Tremulis' plant tour and his reaction to seeing the "Tin Goose" for the first time:

“Here we saw embryonic shapes in raw sheet metal coalescing into the frame and part of the body of an automobile. A nearby drop hammer pounded sheet metal from flat to contoured with ear-splitting vibrations, and the junctions of formed sheet and frame were fused under the bright sparks of welding torches. Elsewhere, men at work stations devoted themselves to the mechanical details of torching, cutting, bending, and drilling the parts of a prototype automobile. Alex [Tremulis} gave us a cursory introduction to all of this and then led us to the design area.

Since he had accepted the position of chief stylist in January, Alex had brought the design of the Tucker automobile from the nebulous to the three-dimensional. He had developed a firm layout of the car which he showed us in a 1/8 size drawing, with every outside and inside dimension carefully indicated.”

So, even though Alex Tremulis had said to Phil Egan that he felt the Tin Goose's body was 95% complete before the Lippincott arrival, it's probable he meant that it was 95% complete towards the design as it stood at that time. It's also entirely possible that it was also 95% complete during its refinement period while the Lippincott team was in-house, even through all its layers of modifications, right up until its introduction. Much like shoveling snow off a driveway in a snowstorm, it never really is finished.

After the Lippincott team's styling contributions were completed on May 3, and before the Tin Goose introduction on June 19, Egan further clarified Tremulis' role: "Alex Tremulis was primarily responsible for guiding the fabrication of the Tin Goose to conclusion. He was privy to Preston Tucker's decisions regarding those portions of the no. 1 and no. 2 clay models that would be shown to the public. The logistics were mind-boggling. Alex had to coordinate his collegues in sheet metal forming, body engineering, engine and drivetrain design, interior furnishings, instrumentation/controls and painting to produce the final product to the satisfaction of the boss. It had to be beautiful, it had to be convincing and it had to run." - Phil Egan, Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile, 1989

J. Gordon Lippincott had stated that once the clay models were completed (May 3, 1947) it was left to Tucker and Tremulis to assemble the prototype and the cars themselves. Lippincott's involvement was over. Phil Egan and J. Gordon Lippincott both were in agreement that "Tremulis deserves most of the credit for the car design, but that the front and back of the car reflect the Lippincott team's work." Lippincott continued, "it's hard to pinpoint responsibility when many designers have a hand in a project."

In any case, It's very clear that the Tucker '48 represents the best design elements from each of the designers that contributed to its creation, and each of them, George Lawson, Alex Tremulis, Budd Steinhilber, Hal Bergstrom, Read Viemeister, Tucker Madawick, Phil Egan and Audrey Moore got it right when the final design rolled out of the Tucker manufacturing plant. The car would not have been the same without any one of their design inputs and should be celebrated as such.

So here's a look at the individual design elements that made the Tin Goose and their evolution from initial design to the Tin Goose to the production Tucker '48s...

On March 11 the Lippincott team arrived at the Tucker plant, led by Hal Bergstrom and accompanied by additional designers Budd Steinhilber, Tucker Madawick, Read Viemeister and Phil Egan. Here's how Phil Egan described Alex Tremulis' plant tour and his reaction to seeing the "Tin Goose" for the first time:

“Here we saw embryonic shapes in raw sheet metal coalescing into the frame and part of the body of an automobile. A nearby drop hammer pounded sheet metal from flat to contoured with ear-splitting vibrations, and the junctions of formed sheet and frame were fused under the bright sparks of welding torches. Elsewhere, men at work stations devoted themselves to the mechanical details of torching, cutting, bending, and drilling the parts of a prototype automobile. Alex [Tremulis} gave us a cursory introduction to all of this and then led us to the design area.

Since he had accepted the position of chief stylist in January, Alex had brought the design of the Tucker automobile from the nebulous to the three-dimensional. He had developed a firm layout of the car which he showed us in a 1/8 size drawing, with every outside and inside dimension carefully indicated.”

So, even though Alex Tremulis had said to Phil Egan that he felt the Tin Goose's body was 95% complete before the Lippincott arrival, it's probable he meant that it was 95% complete towards the design as it stood at that time. It's also entirely possible that it was also 95% complete during its refinement period while the Lippincott team was in-house, even through all its layers of modifications, right up until its introduction. Much like shoveling snow off a driveway in a snowstorm, it never really is finished.

After the Lippincott team's styling contributions were completed on May 3, and before the Tin Goose introduction on June 19, Egan further clarified Tremulis' role: "Alex Tremulis was primarily responsible for guiding the fabrication of the Tin Goose to conclusion. He was privy to Preston Tucker's decisions regarding those portions of the no. 1 and no. 2 clay models that would be shown to the public. The logistics were mind-boggling. Alex had to coordinate his collegues in sheet metal forming, body engineering, engine and drivetrain design, interior furnishings, instrumentation/controls and painting to produce the final product to the satisfaction of the boss. It had to be beautiful, it had to be convincing and it had to run." - Phil Egan, Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile, 1989

J. Gordon Lippincott had stated that once the clay models were completed (May 3, 1947) it was left to Tucker and Tremulis to assemble the prototype and the cars themselves. Lippincott's involvement was over. Phil Egan and J. Gordon Lippincott both were in agreement that "Tremulis deserves most of the credit for the car design, but that the front and back of the car reflect the Lippincott team's work." Lippincott continued, "it's hard to pinpoint responsibility when many designers have a hand in a project."

In any case, It's very clear that the Tucker '48 represents the best design elements from each of the designers that contributed to its creation, and each of them, George Lawson, Alex Tremulis, Budd Steinhilber, Hal Bergstrom, Read Viemeister, Tucker Madawick, Phil Egan and Audrey Moore got it right when the final design rolled out of the Tucker manufacturing plant. The car would not have been the same without any one of their design inputs and should be celebrated as such.

So here's a look at the individual design elements that made the Tin Goose and their evolution from initial design to the Tin Goose to the production Tucker '48s...

REAR GRILLE

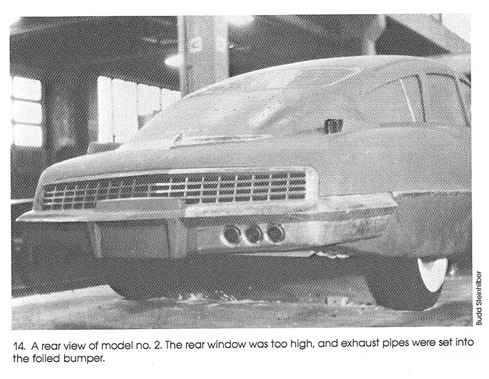

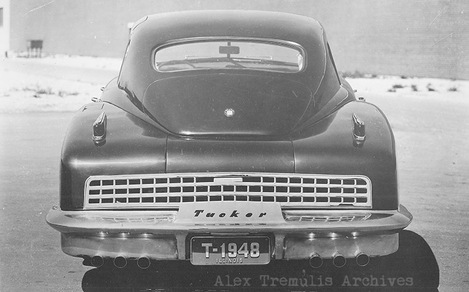

The rear grille of the Tucker '48 perhaps best exemplifies how each of the designers involved with the Tucker were able to contribute to the final design for the rear end of the car. And it clearly happened in a 'round about way over many months of design variations.

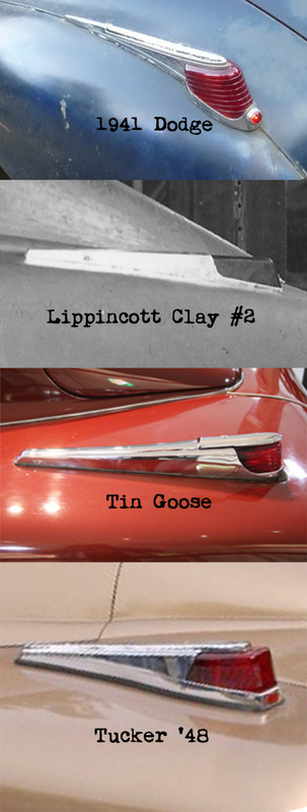

TAILLIGHTS

Such a simple part of the car, yet it carries with it some significant confusion. As Alex Tremulis was quoted in The Indomitable Tin Goose, "They [Lippincott] worked on that model several months, and when they got through the only part of their design that was used was the two taillight castings. They were undoubtedly the most expensive taillights in automotive history".

Tremulis' sense of humor and possible shared frustration with slow progress may have been taken out of context by the author, Charles Pearson, as it has already been pointed out that the Lippincott team provided significant input towards the final design of the Tucker '48, however Tremulis was probably accurate about the cost of the taillights. The Tin Goose's taillights are the only two castings (possibly machined?) in existence, and vendors were known to overcharge Tucker for products and services.

Tremulis' sense of humor and possible shared frustration with slow progress may have been taken out of context by the author, Charles Pearson, as it has already been pointed out that the Lippincott team provided significant input towards the final design of the Tucker '48, however Tremulis was probably accurate about the cost of the taillights. The Tin Goose's taillights are the only two castings (possibly machined?) in existence, and vendors were known to overcharge Tucker for products and services.

Phil Egan described the taillights in Design and Destiny: "Our idea of a long bright metal form with a lens at the end, resting on top of each rear fender, became a cause celebre. A number of Tucker personages put in their two cents on how it could be achieved. It was really quite simple: use a chromium-plated die casting for the front part and acrylic plastic molded in clear red for the lens. It would require die casting and injection molds costing probably eight thousand dollars at the time, a pittance compared to the tooling costs for an automobile. However, we soon discovered a reluctance on the part of the company to undertake such a specialized custom artifact. Due to time and financial constraints, almost all of the parts for the Tucker '48 were going to be bought outside and brought into the plant to be assembled. Thus the solution was to seek an existing tail light design and plan on using it. A pre-war Dodge design was eventually used".

But neither the taillights on the Tin Goose nor on any of the Tucker '48's appear to be off-the-shelf Dodge lights, so perhaps custom (and expensive) castings were made for both the Tin Goose and the subsequent cars.

But neither the taillights on the Tin Goose nor on any of the Tucker '48's appear to be off-the-shelf Dodge lights, so perhaps custom (and expensive) castings were made for both the Tin Goose and the subsequent cars.

1941: The taillights for the 1941 Dodge Business Coupe and Luxury Liner are immediately recognizable as leading to the design on the Tucker '48's back end. It doesn't appear as if the curvature on the stock Dodge taillight would match the contour of the Tucker's fender.

May 4, 1947: The taillights on Clay #2 were modernized versions of the Dodge taillights, with a sleeker profile, squared-off edges, and a much cleaner look.

June 18, 1947: These unique Tin Goose taillights reverted back to the 1941 Dodge design, with a more rounded look and a heavy chrome cap to hold the lens in place, but they don't appear to be from Dodge. These are the only two known taillights of this design, so Tremulis' comments as to their cost may have been right on target.

Tucker '48: The final taillight design was similar to the sleek Lippincott design on Clay #2, with the leading edge lens angle reversed, combined with the top cap similar to the 1941 Dodge.

Even then, though, it wasn't over. The first 25 cars had one casting and due to a rear fender shape change, the last 25 cars were finished with a different contour to the casting. So, yes, the Tucker tail lights were probably the most expensive in automotive history!

May 4, 1947: The taillights on Clay #2 were modernized versions of the Dodge taillights, with a sleeker profile, squared-off edges, and a much cleaner look.

June 18, 1947: These unique Tin Goose taillights reverted back to the 1941 Dodge design, with a more rounded look and a heavy chrome cap to hold the lens in place, but they don't appear to be from Dodge. These are the only two known taillights of this design, so Tremulis' comments as to their cost may have been right on target.

Tucker '48: The final taillight design was similar to the sleek Lippincott design on Clay #2, with the leading edge lens angle reversed, combined with the top cap similar to the 1941 Dodge.

Even then, though, it wasn't over. The first 25 cars had one casting and due to a rear fender shape change, the last 25 cars were finished with a different contour to the casting. So, yes, the Tucker tail lights were probably the most expensive in automotive history!

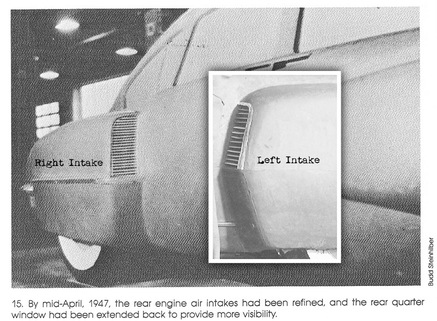

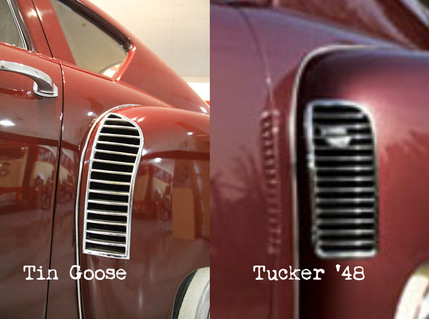

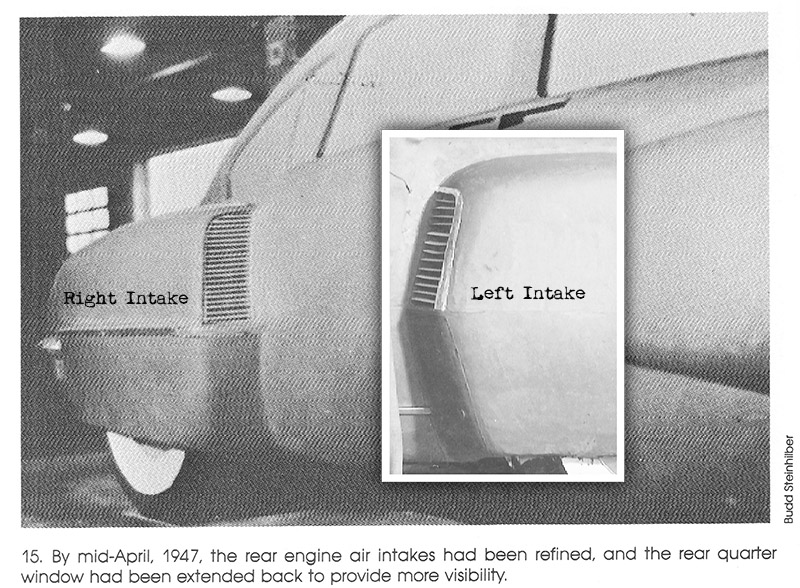

REAR AIR INTAKE

Towards the end of Lippincott's involvement, Phil Egan detailed how the rear intakes evolved: "The two competing projects [Tremulis' Clay #1 and Lippincott's Clay #2] had become increasingly interdependent. It simply wasn't possible for each to ignore the travails of the other. Alex didn't ignore what we were doing and made many suggestions which helped us. We, in turn, contributed a few ideas to him; certainly a just aid to a worthy compatriot. A constrained delicate and very successful rear fender air intake on the #1 clay model was one of the results of this cooperative effort. Ultimately, it was Alex's accomplishment, but Read [Viemeister] and Budd [Steinhilber] contributed ideas which helped carry it off."

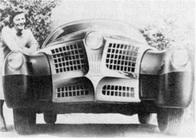

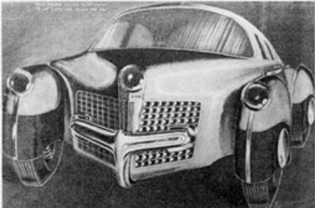

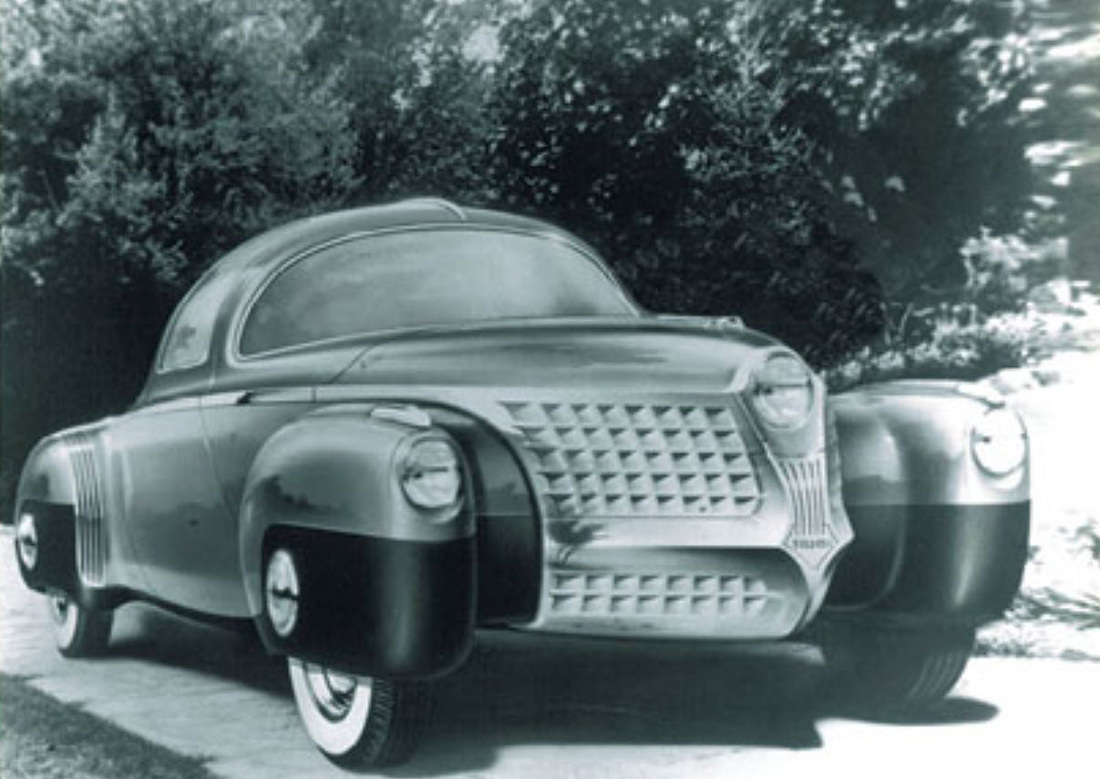

FRONT GRILLE AND BUMPER

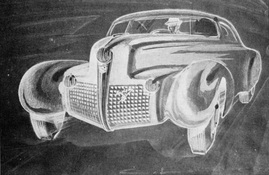

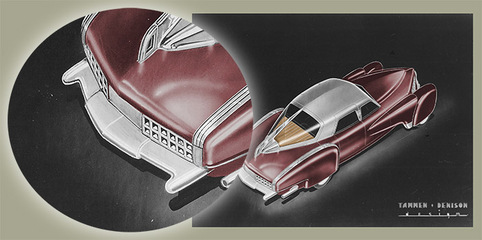

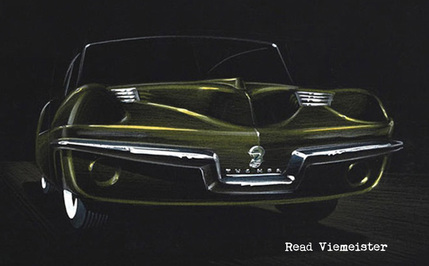

The evolution of the front bumper and grilles resulted in the now-legendary steerhorn front bumper that identifies the car as a Tucker '48. The creativity that Read Viemeister displayed in his initial proposal that included the bumper was key to finishing off the front end design that never was quite complete despite the efforts by Lawson and Tremulis before. It wouldn't be until just before the Lippincott team left that the front bumper and grille design would all come together.

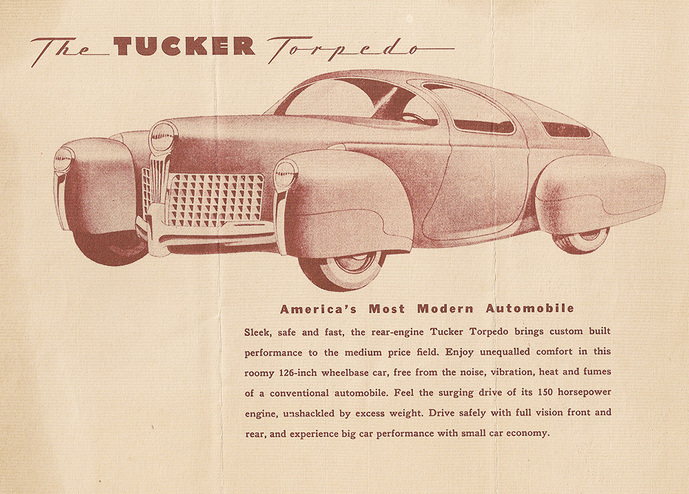

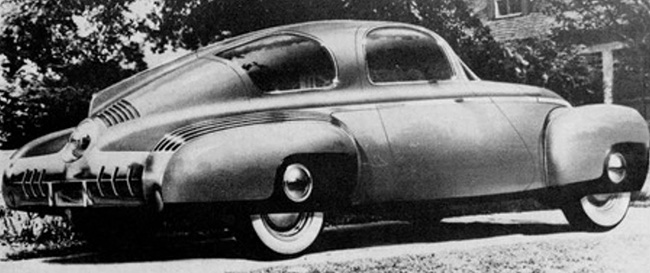

OVERALL SILHOUETTE

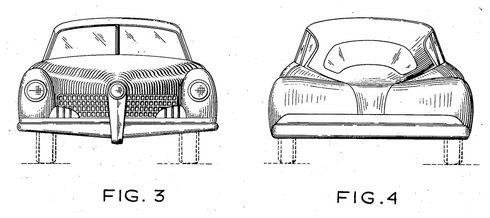

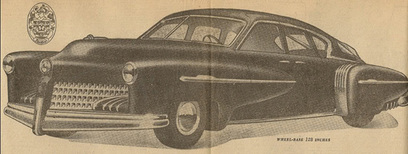

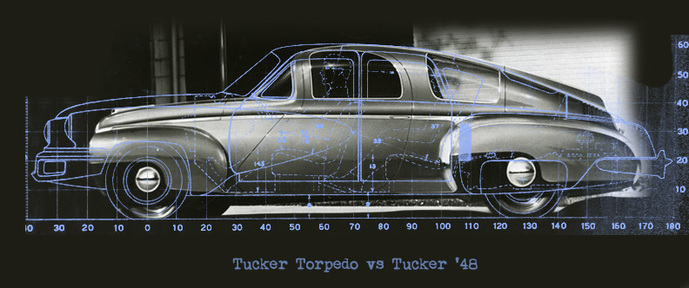

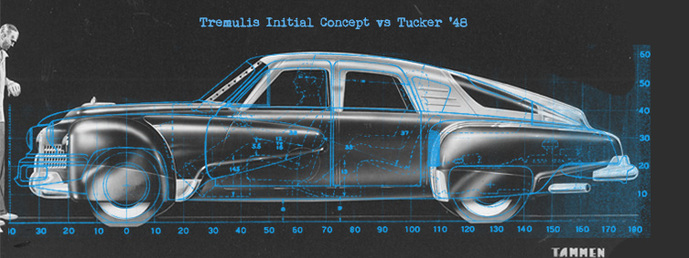

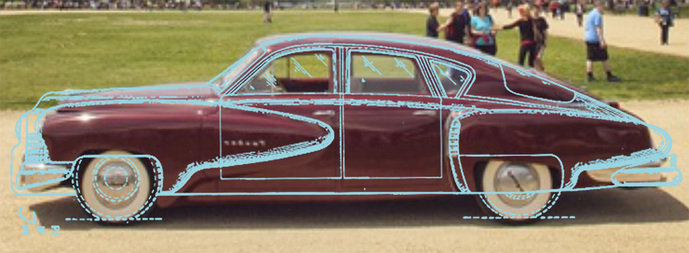

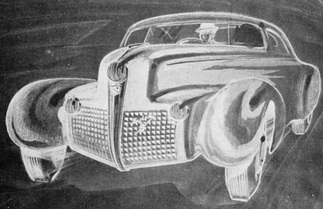

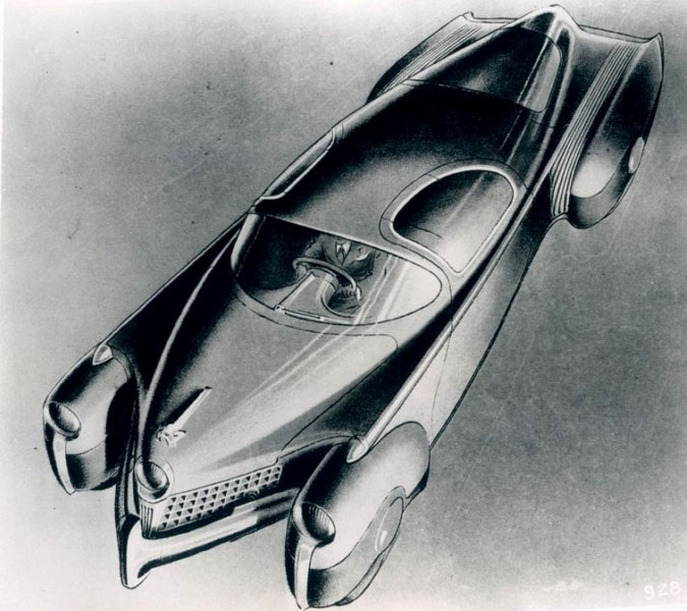

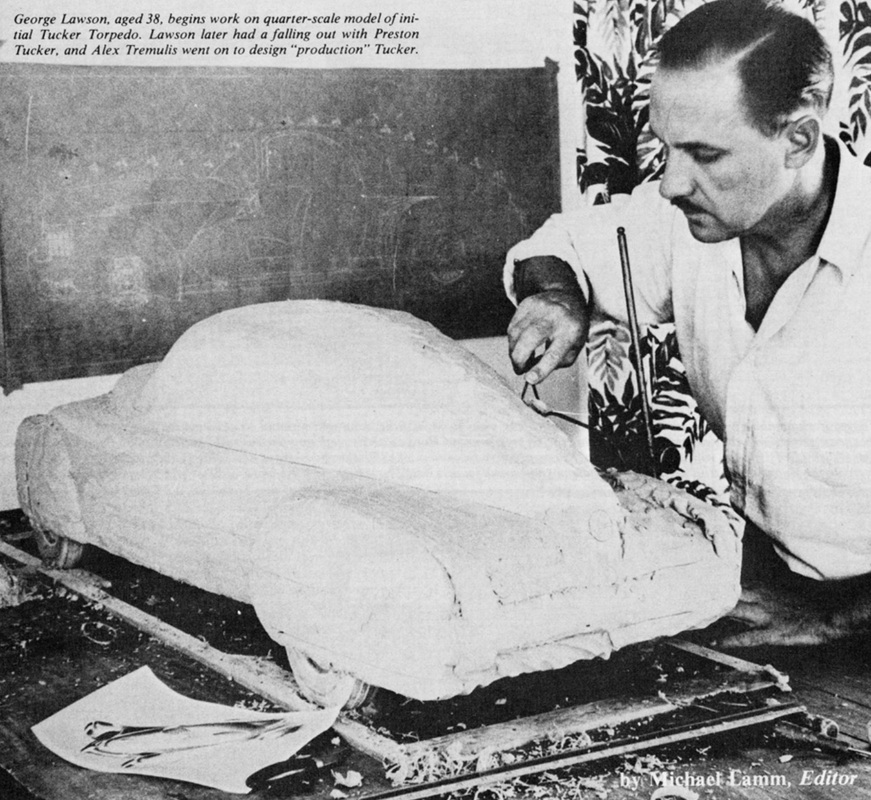

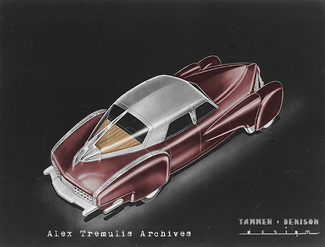

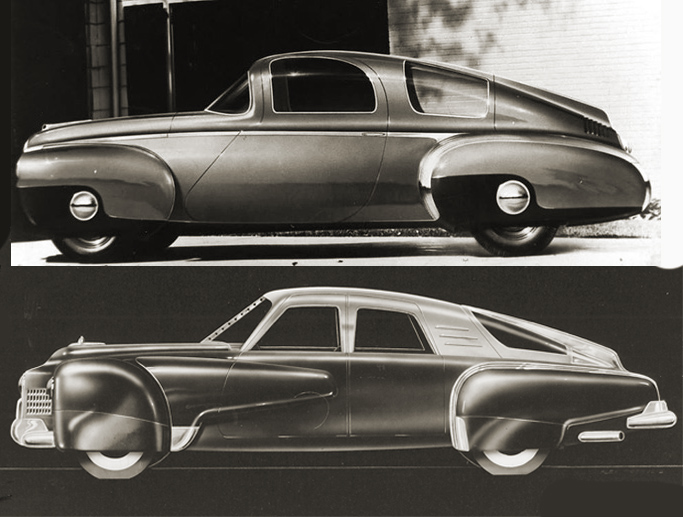

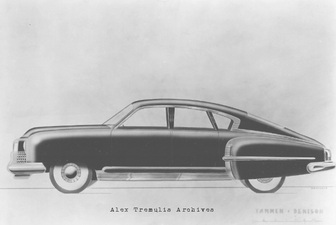

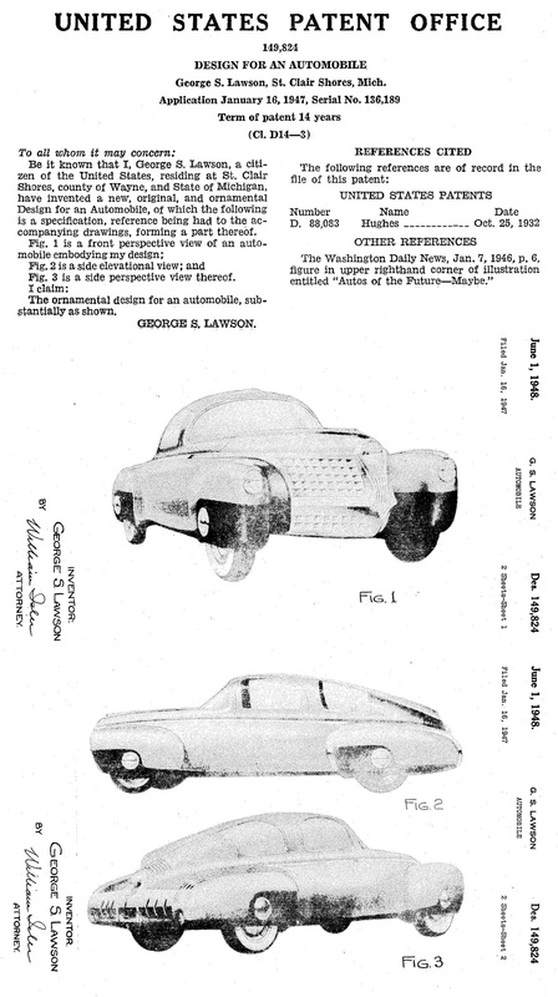

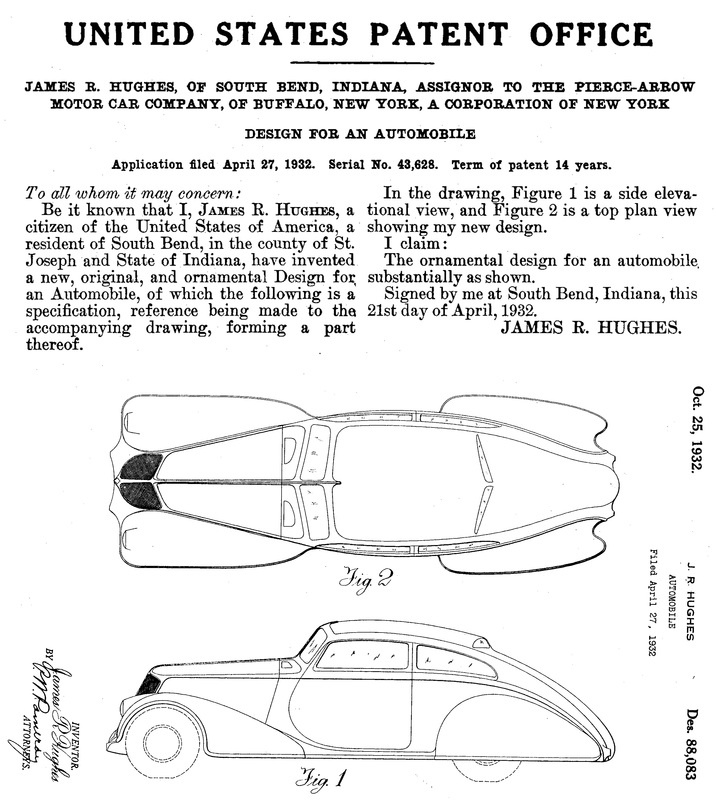

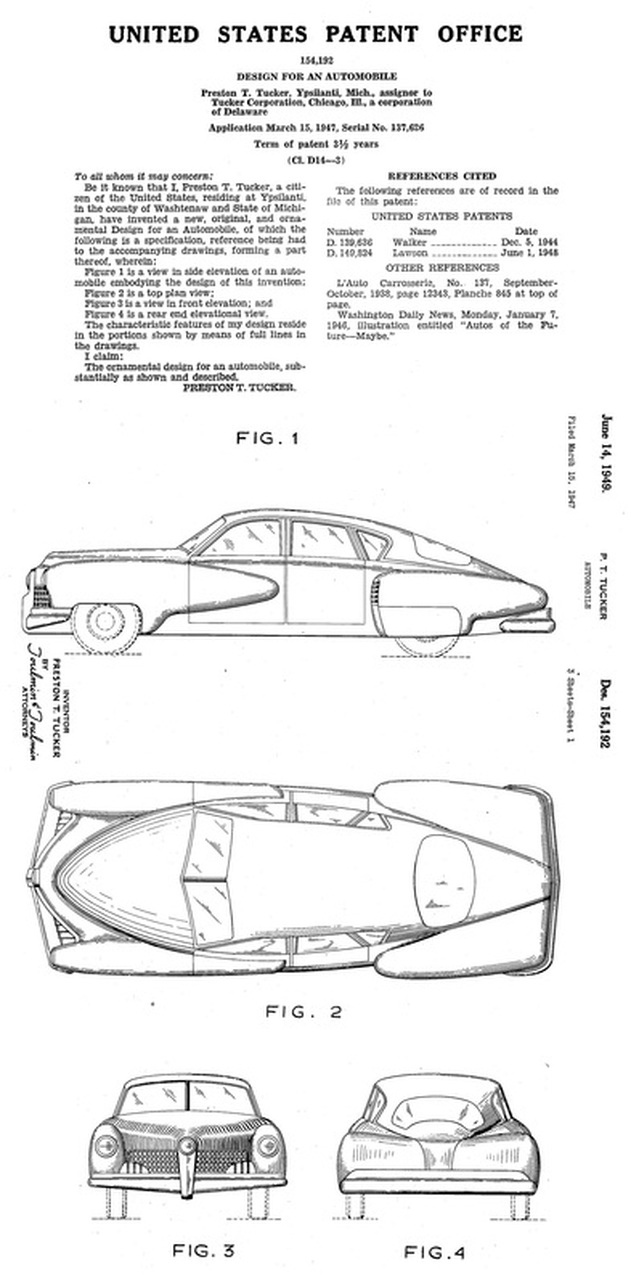

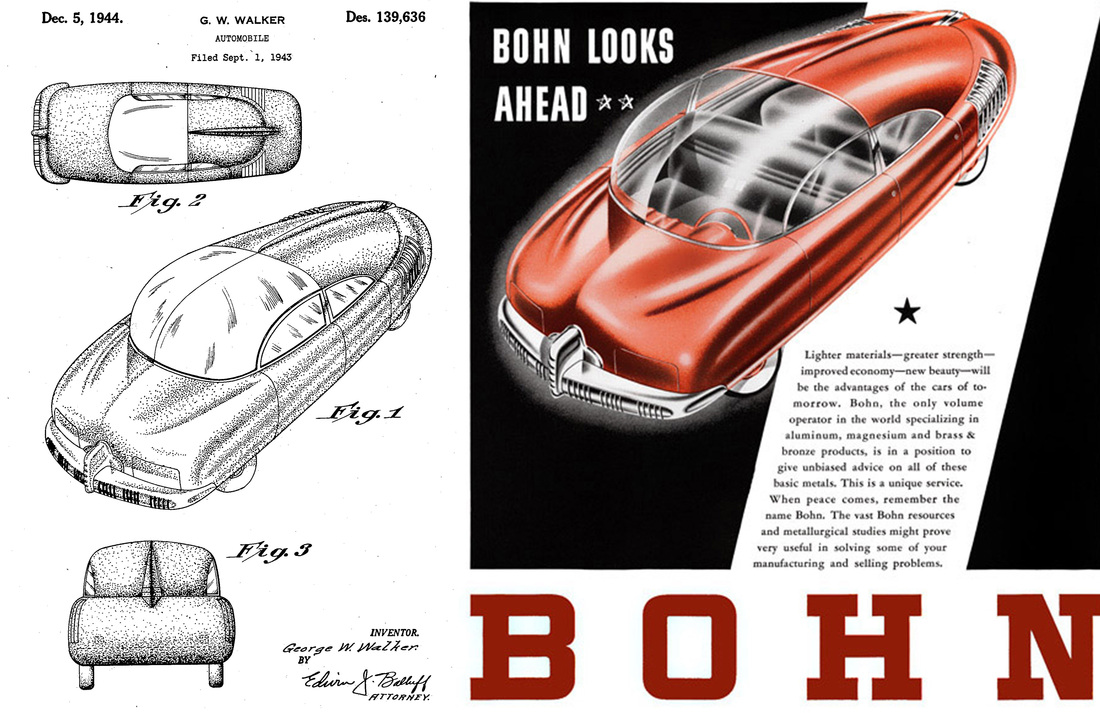

As was described in The Indomitable Tin Goose, the basic outline for the side silhouette of the car was dimensionally worked out by Tucker's planners in December 1946. It would be these same dimensions that Tremulis would use for his first sketches and the ones that went into the build for the Tin Goose. So it's no surprise that the passenger compartment for the Tucker '48 follows those same dimensions that harken back to George Lawson's Torpedo design.

The windshield (and probably the firewall) was moved forward approximately 10 inches, but the roofline profile of the final design for the Tucker '48 (in blue) as of September 1947 matches the roofline for George Lawson's plaster model for the Torpedo. Every design in-between matches, as well, including Tremulis' original sketches from January, Tremulis' advertisements for March, the March patent illustrations, the Lippincott Clay #2 (and presumably Tremulis' Clay #1), and finally, the Tin Goose.

So, Charles Pearson's account for their work in December 1946 appears to be an accurate account, at least for the cabin: "The dimensions set up at this time were, with few exceptions, the ones that were used in the final body design. There was no great attempt at styling, though the side silhouette was nearly identical with the finished design. An extra four inches were allowed on wheelbase, because Tucker was still insisting on fenders that turned with the wheels, and the production man said there would be plenty of time to talk him out of that later." - Charles Pearson, The Indomitable Tin Goose, 1960

As a quick check, comparing Tremulis' very first renderings for Preston Tucker in December 1946 to the final tooling dimensions as of September 1947, the dimensions remained little changed throughout all the development of the Tin Goose and the production Tuckers, confirming Pearson's accounting of events. It also serves to highlight Tremulis' innate ability to pull off some remarkable styling, moveable fenders or fixed, while remaining within the confines of fixed dimensions. A closer look reveals that the doors, window locations, and fender contours for the final design were changed very little from his initial reactions to the car, further suggesting that those dimensions were frozen.

So, Charles Pearson's account for their work in December 1946 appears to be an accurate account, at least for the cabin: "The dimensions set up at this time were, with few exceptions, the ones that were used in the final body design. There was no great attempt at styling, though the side silhouette was nearly identical with the finished design. An extra four inches were allowed on wheelbase, because Tucker was still insisting on fenders that turned with the wheels, and the production man said there would be plenty of time to talk him out of that later." - Charles Pearson, The Indomitable Tin Goose, 1960

As a quick check, comparing Tremulis' very first renderings for Preston Tucker in December 1946 to the final tooling dimensions as of September 1947, the dimensions remained little changed throughout all the development of the Tin Goose and the production Tuckers, confirming Pearson's accounting of events. It also serves to highlight Tremulis' innate ability to pull off some remarkable styling, moveable fenders or fixed, while remaining within the confines of fixed dimensions. A closer look reveals that the doors, window locations, and fender contours for the final design were changed very little from his initial reactions to the car, further suggesting that those dimensions were frozen.

And that helps to explain the activity in the photographs (below) from within Tremulis' styling studio during the early build of the Tin Goose. The full-scale drawing on the back wall of the studio supports the accurate dimensions for the initial building of the Tin Goose, going direct to metal, while the small 1:10 scale clay model provided the necessary dimensions for the design change to the fixed fenders with the flowing pontoon fenders. Most likely, the other gentlemen in the photo with Tremulis (front right) are Tucker's expert metal shapers, Al McKenzie, Herman Rigling, William Stampfli and possibly Emil Deidt.

It appears that a new full-sized drawing is being prepared of the flowing fendered design that became the Tin Goose. This also would explain why there were several layers of metal on the Tin Goose, where they had changed from the initial drawings to the fixed fender design, to the small sheet metal changes provided by the two full-sized clay models during the Lippincott team's residency. It's clear the metal body of the Tin Goose was evolving from the beginning and constantly changing throughout the first half of 1947, up until its introduction in June of 1947.

It appears that a new full-sized drawing is being prepared of the flowing fendered design that became the Tin Goose. This also would explain why there were several layers of metal on the Tin Goose, where they had changed from the initial drawings to the fixed fender design, to the small sheet metal changes provided by the two full-sized clay models during the Lippincott team's residency. It's clear the metal body of the Tin Goose was evolving from the beginning and constantly changing throughout the first half of 1947, up until its introduction in June of 1947.

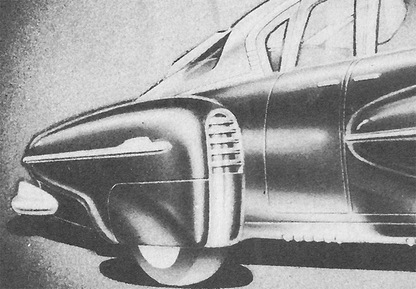

REAR FENDERS and SIDE WINDOWS

The rear fenders are best compared to Tremulis' drawings used for the March 1947 advertisements for the Tucker '48, since that is what has been described as the foundation for Clay #1. So the most suitable scale side profile drawing comes back to the March 15 1947 patent filing for the Tucker '48. Comparing Tremulis' rear fender to the patent filing shows a near-perfect match of contours and intake location. Additionally, the side windows on the Tin Goose are in the exact locations as the patent drawing (in blue). Tremulis had said that as of March 1947, a million dollars had already been spent on the tooling for the locked dimensions on the rear of the car, and this comparison confirms that the design had not changed from at least as early as February 1947 through the June introduction of the Tin Goose.

Both sides of the Lippincott Clay #2 show a markedly different profile to the rear fenders on the Tin Goose. The leading edge was more of an arrowhead design than the fully curved contour of Tremulis' advertising and the patent application. Similarly, the opera windows on both sides of the Lippincott Clay #2 show they were extended more rearward for improved visibility than the Tin Goose. Phil Egan had mentioned that the left side of Clay #2 was only used as potential styling for a 1950's model. It very well may be that the rear of the Tin Goose was already complete by this time which would explain why the extended windows were not implemented on either the Tin Goose or the Tucker '48. Tremulis wouldn't reintroduce the better visibility of the wrap-around rear window until much later in 1948, so it wasn't because there was a better design in the works.

FRONT FENDERS

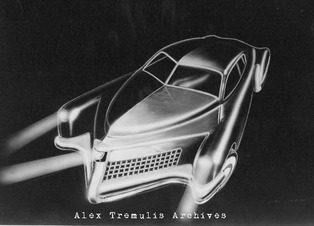

The shape of the front fenders, along with the Cyclops headlight, are some of the unique features that immediately identify the Tucker automobile. The front fenders changed very little from the time Tremulis arrived on the scene to the final closing of the doors. Their length and top profile were consistent from start to finish, with slight modifications to the lower contours, but remained faithful to Tremulis' vision.

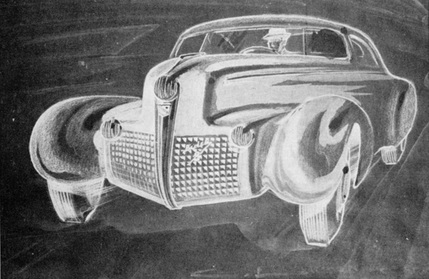

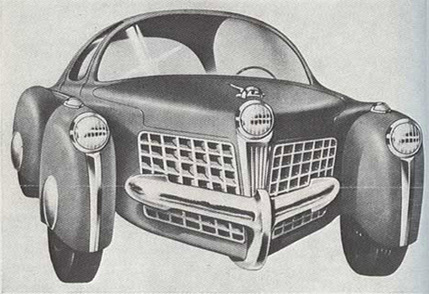

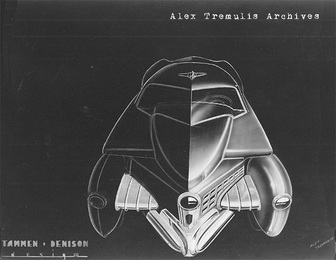

January 1947: Alex Tremulis' first series with the moveable front fenders.

February 1947: The fixed-fender design as used for advertising.

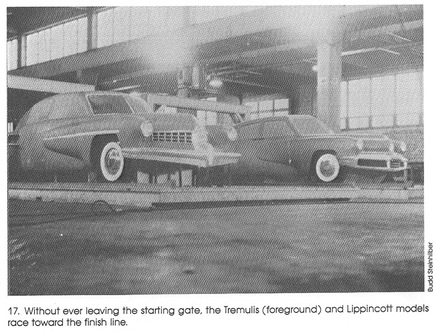

April 1947: Tremulis' Clay #1 in the foreground and the right side of Lippincott's Clay #2 both carry Tremulis' sweeping pontoons.

June 1947: The Tin Goose, now with all the side chrome eliminated.

March 1948: The Tucker '48 again with the pontoons closely mimicking Tremulis' contours of February 1947, just slightly more pointed than those on the Tin Goose.

So it's evident that Tucker's synergistic design process brought together elements in such a way that the final design as a whole is so much better than had any one of its contributors built the car in a vacuum without critique or reflection. Perhaps that is part of Preston Tucker's genius in bringing together such talented individuals: That regardless of opinion of authorship, they could combine talents to create one of the most revolutionary designs the automotive industry had yet to see...

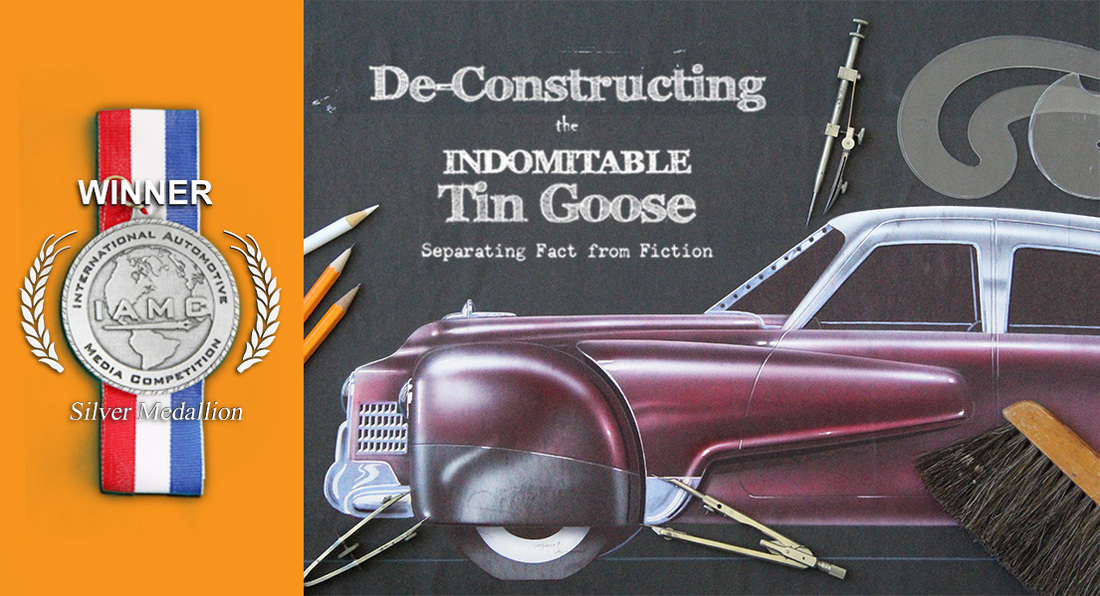

REQUIRED READING

| To learn more about Alex Tremulis' involvement with Preston Tucker and the iconic Tucker automobile, just click the photo at left for Part 1... Published in 1960, The Indomitable Tin Goose provides an insider's accounting for the events during much of the building of Tucker's "Car of Tomorrow". The author, Charles Pearson, was Preston Tucker's public relations manager from mid-1946 until the end of 1947. This would be the most active and productive timeframe for the design efforts to build the Tucker '48. The details of Tucker's travails in obtaining the facilities and financing are particularly interesting. Written so that it's readable, despite containing so much historical information that could have been lifeless. |

| Published in 1989 at the height of the popularity of the Francis Ford Coppola movie, Tucker: A Man and His Dream. The author, Phil Egan, was a member of the Lippincott design team that spent two months at Tucker prior to the unveiling of the Tin Goose prototype. Alex Tremulis would later hire Egan directly to help with the many design details that would be needed to produce the 50 Tucker '48's that represent the entire production output from the factory. Many of the great photographs from inside the Tucker walls were provided by Lippincott designer Budd Steinhilber, to document the progress made on the clay models used for styling ideas. |

| A must watch. Very entertaining and fast paced account of the rise and fall of the Tucker Corporation. Nominated for three Academy Awards in Best Supporting Actor (Martin Landau), Best Art Direction (Dean Tavoularis), and Best Costume Design (Milena Canonero), Landau would take home the Oscar. Alex Tremulis was portrayed by actor Elias Koteas, a near-perfect look-alike, for the automobile design veteran. Although fictionalized, it provides a great backdrop to learn more about the Tucker cars and the people that produced them. |

copyright 2014 Steve Tremulis

RSS Feed

RSS Feed