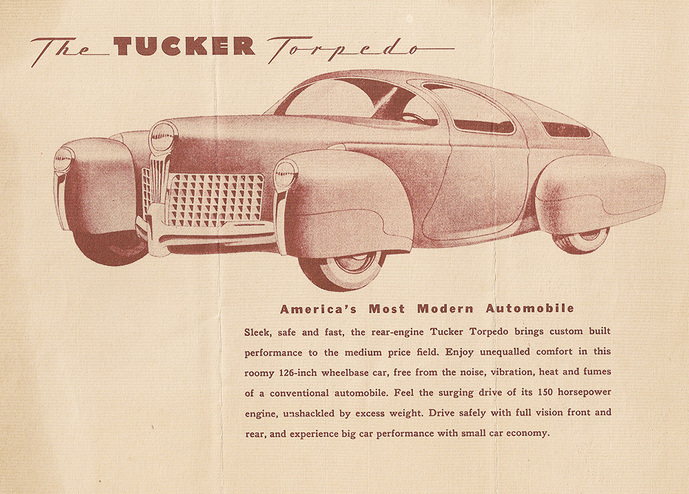

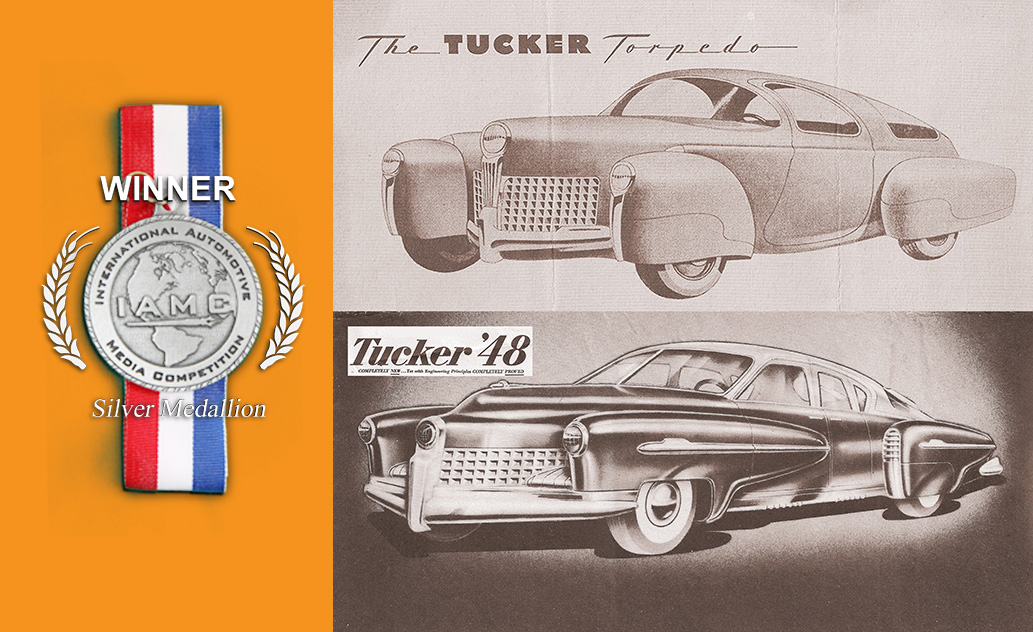

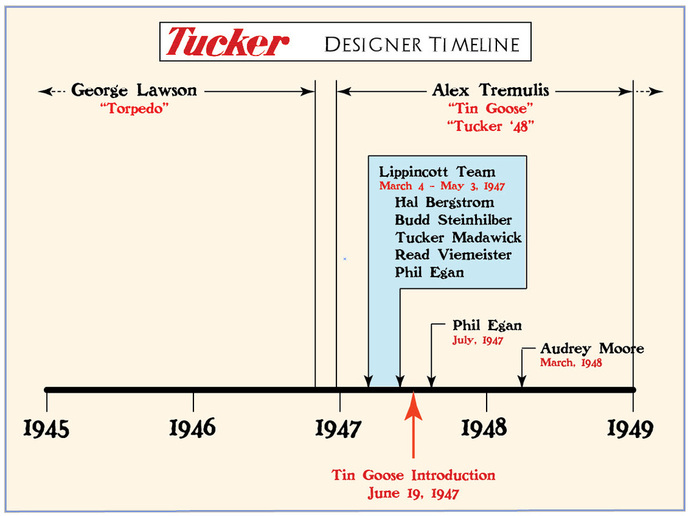

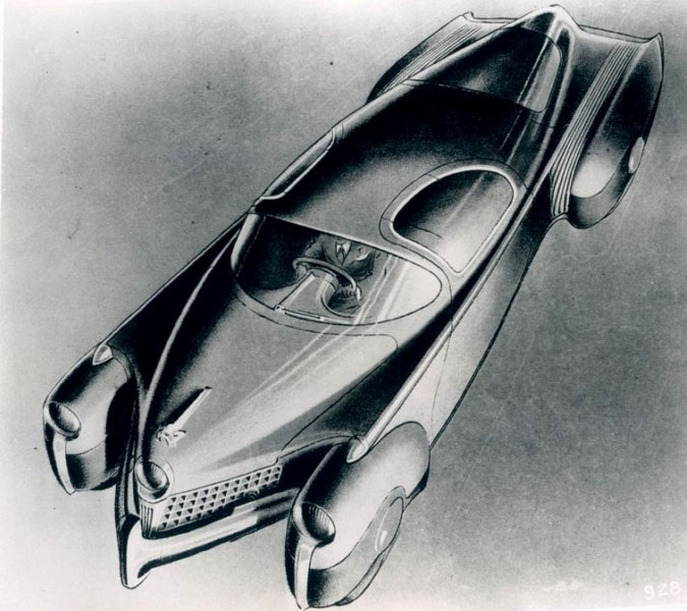

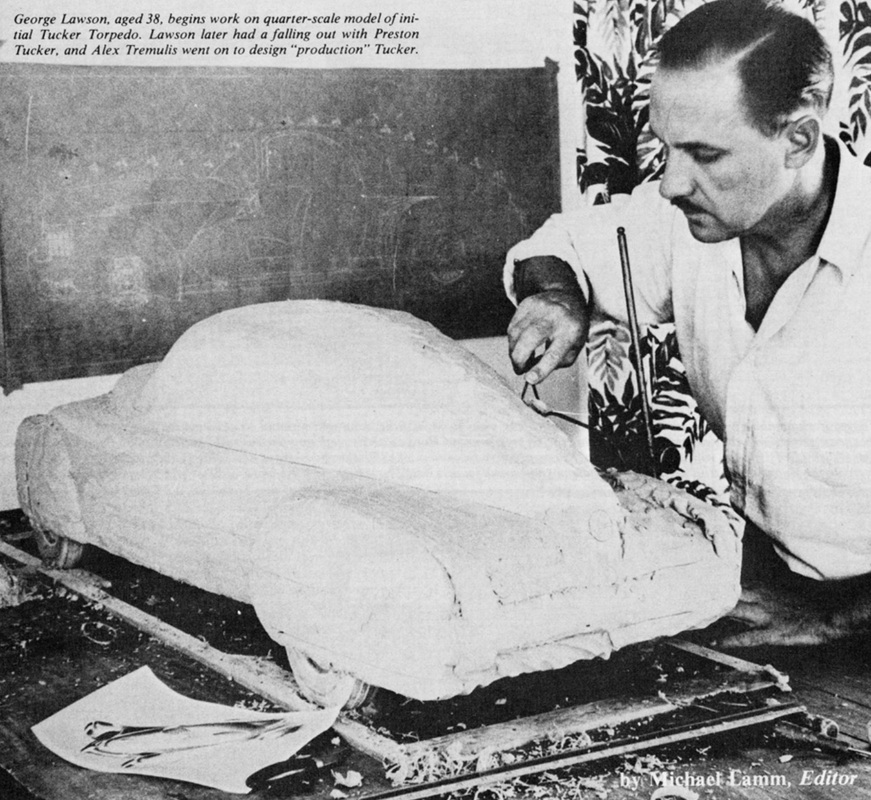

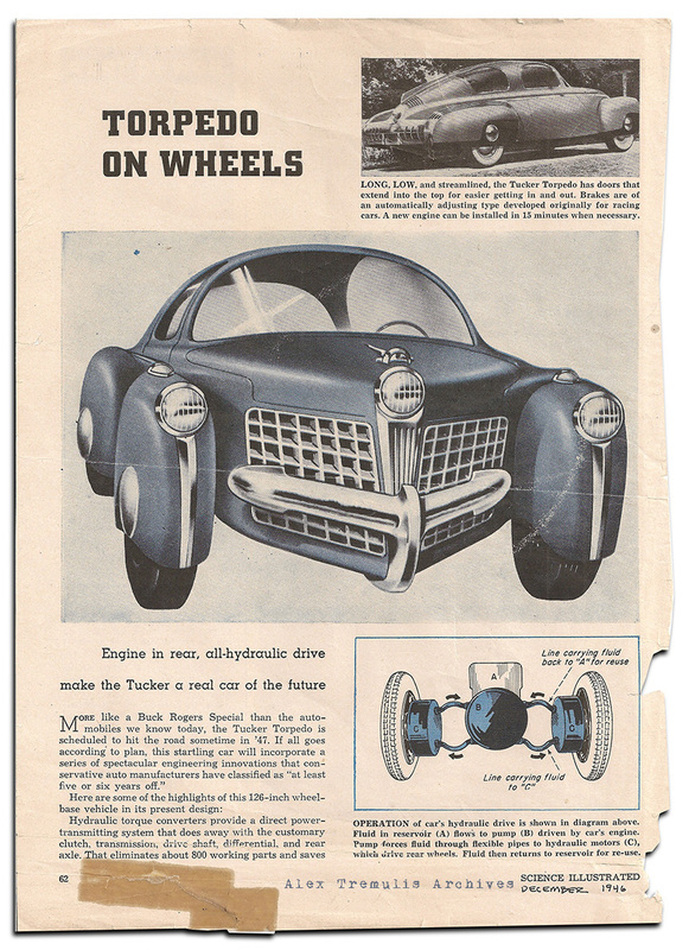

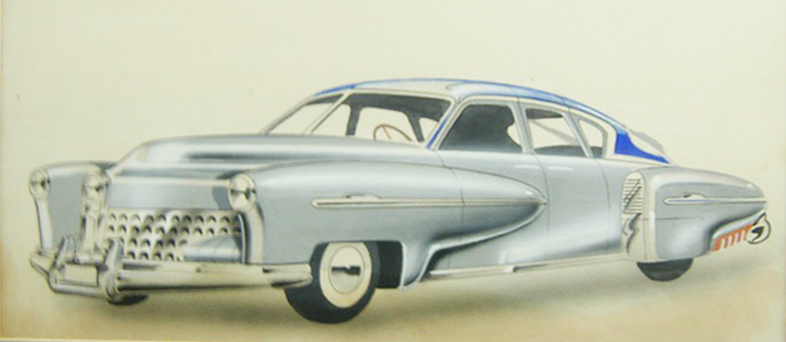

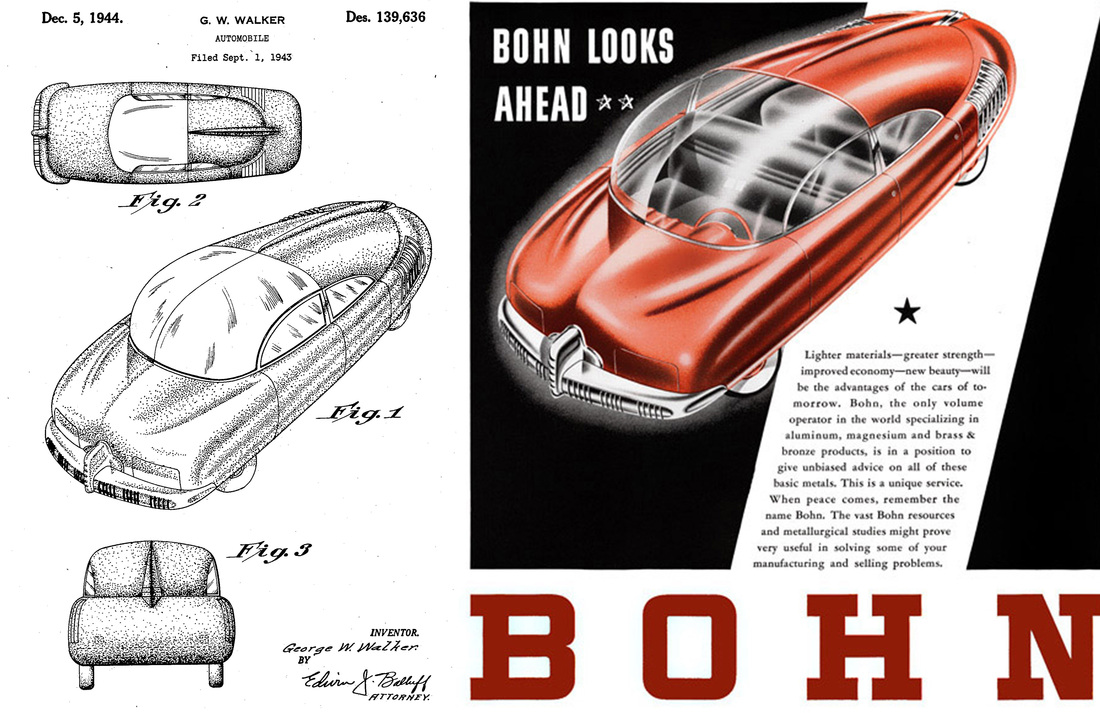

It all started during 1944 when George Lawson would be the first to illustrate what Preston Tucker's "Car of the Future" would look like. Just as all designers are influenced by their prior work, so too was Lawson. He relied upon his earlier work as a GM designer in the Buick division to form his initial drawings for the Tucker Torpedo.

By December 1946, after almost two years, George Lawson and Preston Tucker had a falling out over unkept promises. George Lawson sued Preston Tucker for $50,000 and presumably Tucker countered that he still had no car to show after almost two years' effort. The matter was eventually settled out of court with Tucker reportedly paying Lawson a $10,000 settlement.

In 1960, Charles Pearson described his frustrations inside Tucker's design studio, and directed his anger squarely at Lawson: "Early in December [1946], during the lull in the housing fight, I was complaining to one of the top men planning production that I wished to hell we had something better than the lousy art work we were using, because it was getting tougher to sell every day. It was too arty and stylized to start with and, worse, still, even a layman could see that it was a long way from the six-passenger sedan Tucker said he was going to build.

The production man said he was just as disgusted as I was, and if he had even an idea as to what the body and chassis were going to look like he could at least start figuring out how to build it. That was what started the first actual work on the final body design, and the entire job was completed in less than a month."

"The dimensions set up at this time were, with few exceptions, the ones that were used in the final body design. There was no great attempt at styling, though the side silhouette was nearly identical with the finished design. An extra four inches were allowed on wheelbase, because Tucker was still insisting on fenders that turned with the wheels, and the production man said there would be plenty of time to talk him out of that later." - Charles Pearson, The Indomitable Tin Goose, 1960

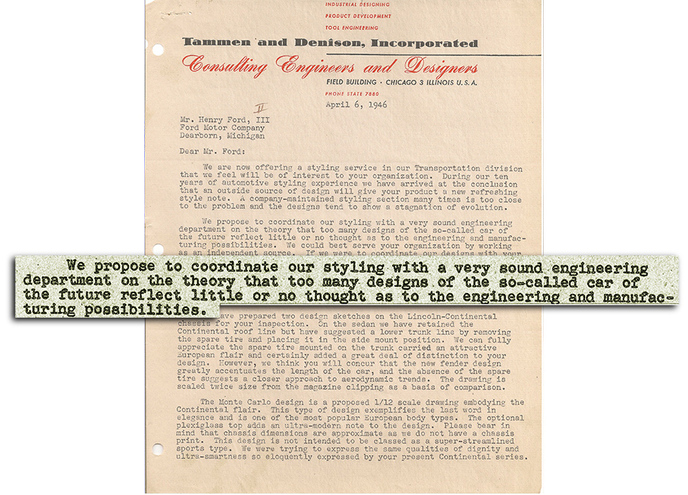

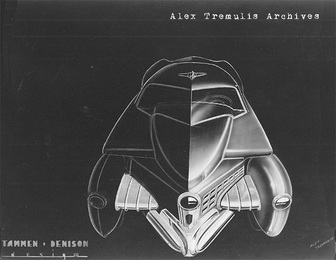

The date of the first meeting Tremulis had with Preston Tucker was described by Charles Pearson in "The Indomitable Tin Goose" as being on Christmas Eve, 1946, but records show it may have actually taken place a few days later, with a call for an appointment on the 27th and a meeting on the 28th with Preston Tucker, Lee Treese (VP of Manufacturing), and Kenneth Lyman (VP of Engineering). At that meeting Lawson's drawings were reportedly discussed. But Tremulis had also described meeting Preston Tucker for the first time at the Drake Hotel on Christmas Eve and again at the offices at Tammen and Denison on New Year's Eve, so it's probable there were a series of meetings at various locations to discuss progress on Tremulis' new designs.

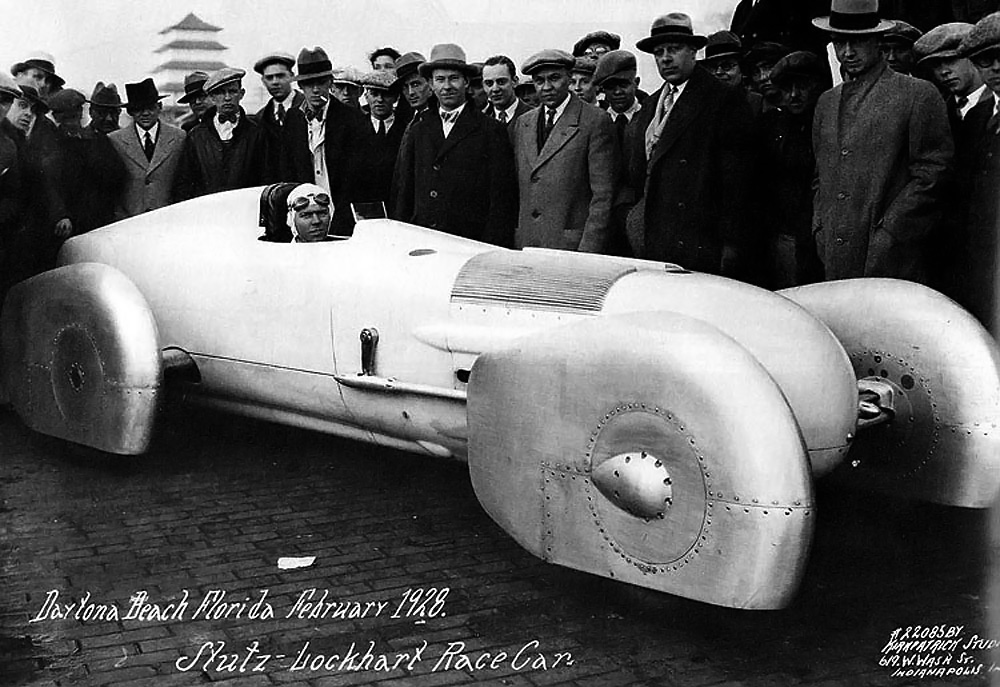

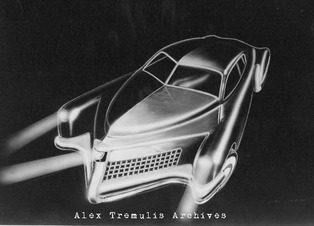

In any case, it was late December when Tremulis finally got an appointment with Preston Tucker. Tremulis had brought along his portfolio of futuristic concept cars. He had a wealth of prior experience as chief stylist at Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg as well as his design and custom builds while at Briggs Manufacturing, American Bantam and Custom Motors of Beverly Hills. By then, Tremulis was also an authority on streamlining, having designed many advanced jet aircraft and guided missiles for the US Army Air Force during World War II, often using the wind tunnel as a design aid. Tremulis' design philosophy of marrying aircraft technology with automobile design was identical to Preston Tucker's vision for his car.

Tremulis' timing was perfect. Preston Tucker, now without a stylist for his car with the unwelcome departure of Lawson, found his car's future designer in Tremulis. At the time, Tremulis was working at the industrial design firm of Tammen and Denison and the Tucker account would give him full authority to pursue his automotive design philosophy. Part of Tremulis' pitch to Tucker was undoubtedly the same as his April 1946 pitch to Henry Ford II.

On January 5, he met again with Preston Tucker, but this time he was joined by Harold Karsten (a/k/a Abe Karatz), Fred Rockelman and Preston Tucker Jr. This was to be a defining moment in automotive history.

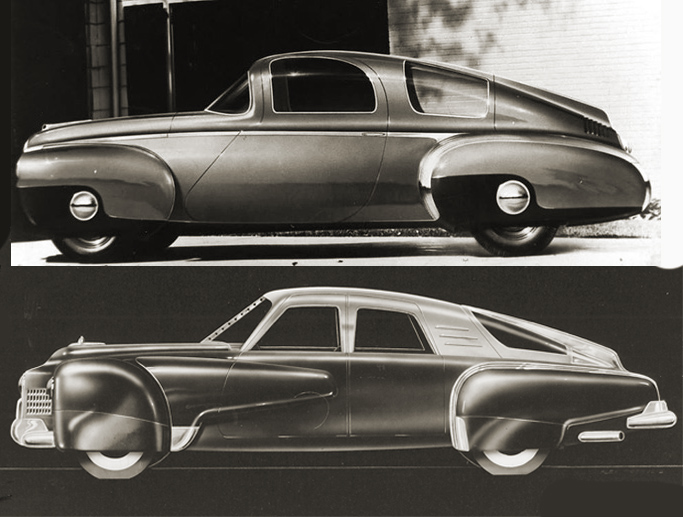

TRANSITIONAL DESIGN

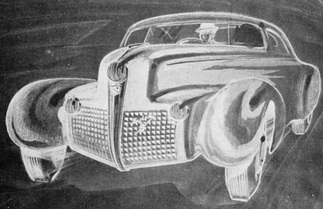

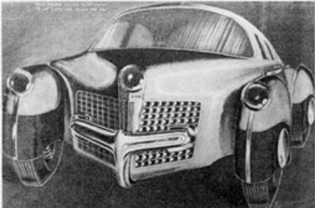

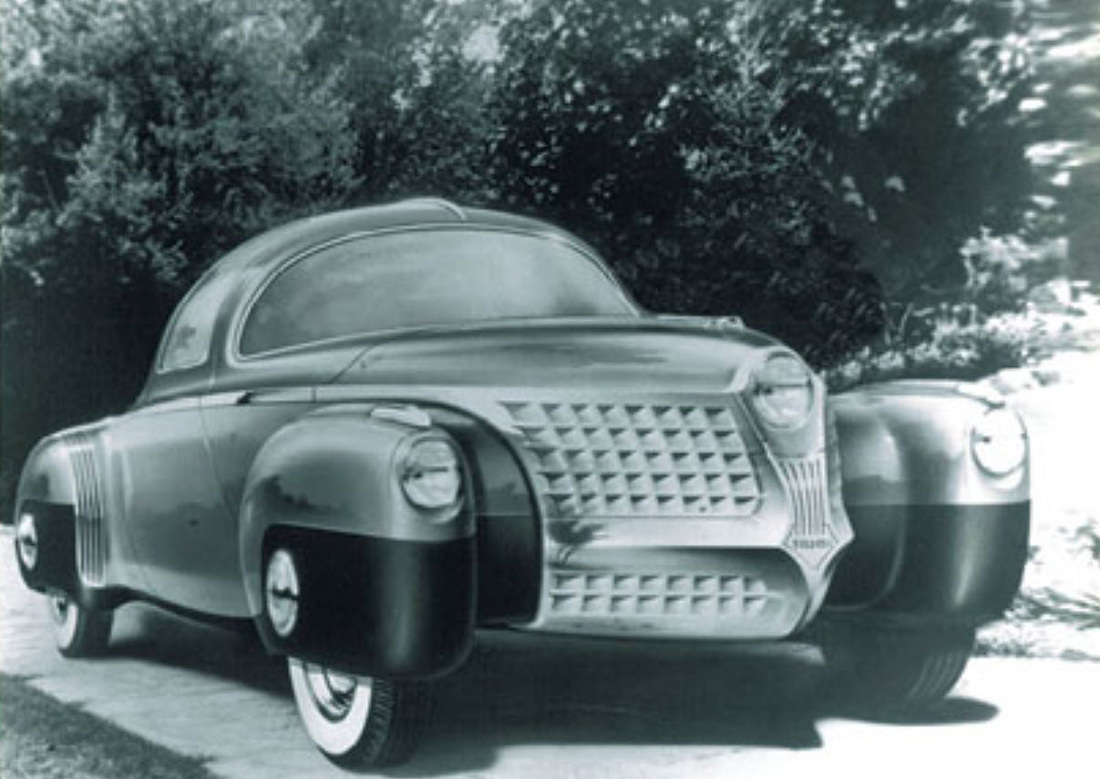

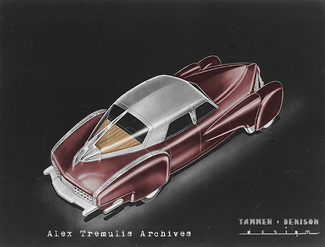

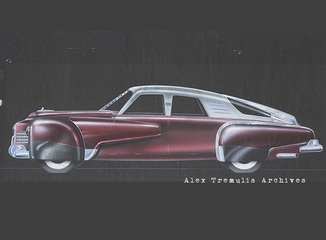

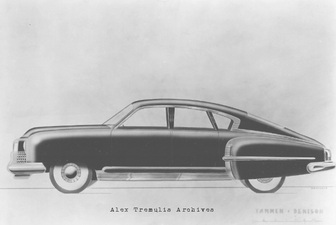

Tremulis had created a series of impressive renderings that fed off of Lawson's design, yet provided more practical design changes for post-war Americans. Specifically, he designed a four-door sedan where the doors opened into the roofline to allow ingress without bumping your head. On the bottom of the doors was a raised rocker panel so that the doors wouldn't hit the curb upon opening. The desire to seat three Chicago Bears linemen in the front and rear mandated a more conventional roofline, lower in the middle and higher on the sides, so that three could sit abreast in either the front or the back seat without the end passengers bumping their heads on the side windows. Each of the fenders sported streamlined sheet metal flowing back from the wheelwell that conveyed a unique blend of the pre-war pontoon fenders with the latest in flat-fendered side treatments.

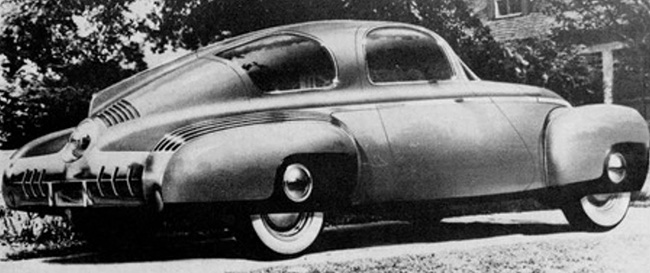

In any case, Tremulis had managed to retain the styling cues and relative dimensions of the Lawson design, yet provided a clear and realistic direction in which to proceed. The moveable front fenders of the Lawson design were retained for the time being, but they would be entirely eliminated within the next few days. Charles Pearson had described the side silhouette of Tremulis' design being very close to the dimensions Tucker's men had laid out and it appears very close to the Torpedo's silhouette as well.

As Alex Tremulis stated, his first task was to eliminate the moveable front fenders in favor of a more conventional design. Time was of the essence and the engineering difficulties in sorting out the cycle fenders did not support Preston Tucker's desire to have a prototype built within 60 days. So Tremulis re-designed the car with conventional fixed fenders, and made the center headlight turn with the wheels. He also eliminated the flowing pontoons from his first design series as he felt they were already dated. And Tremulis wasn't alone in his desire to remove his earlier pontoons. As Charles Pearson described them:

"I liked all except the front fenders which I thought stunk, and said so. My popularity couldn't have dropped faster with a sudden attack of smallpox. Tucker scowled at me for a week, though much later he admitted that at least he agreed with my logic." - Charles Pearson, The Indomitable Tin Goose, 1960.

Preston Tucker liked the first fenders and felt first impressions were usually correct, so the unique pontoons stayed. A great decision, as these characteristic fenders would forever be identified with the Tucker '48.

Tremulis' elegantly simple solution retained the safety factor of being able to see where you're turning, yet significantly shortened the timeline to completion of the first prototype.

TUCKER '48 BODY DESIGN FINALIZED

By January 14 1947, Preston Tucker, Alex Tremulis and Tucker's Vice President of Manufacturing, Lee Treese, were off to source new glass to fit the prototype four-door sedan. By then, the fixed-fenders of the car re-incorporated the flowing pontoons from Tremulis' first design renderings.

So the transition from Lawson's Torpedo design to Tremulis' Tucker '48 design was exceptionally quick. From the date of Tremulis' first reported interview with Preston Tucker to the time when Tremulis' fixed-fender design with flowing fenders first appeared, a maximum of 3 weeks had elapsed. If the first meeting between Tremulis and Tucker was after Christmas Eve and you allow for some time for the first drawings of the final design to have been created, then it looks like the time span of 6 days from initial concept to final design (as has been reported elsewhere) is entirely possible and even more remarkable. Whatever the actual date may have been, from that point on the building of the first prototype would be the focus of everyone involved for the next two months.

As Phil Egan would tell in his book "Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile": "Between the first of January and our [Lippincott Team] spring of 1947, Tremulis had managed a crash program calling for exhausting hours of work by a dedicated crew. They brought an automobile design project from scratch to a recognizable body shape in metal without a clay model (there had been an embryonic 1/8 size clay model of little help). For a production car undertaking this bordered on the ridiculous, but he had done it."

Egan further clarified: "Up until the time of our arrival, all efforts had been directed at forging the metal marvel [Tin Goose]."

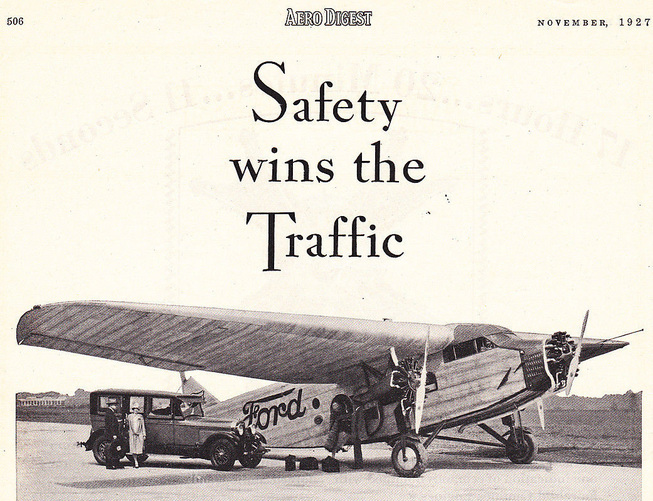

TIN GOOSE

Phil Egan also gave the credit to Alex Tremulis for the naming of Tucker's first hand-built car. The prototype they were working on would be nicknamed the "Tin Goose" out of reverence to Bill Stout's Ford Trimotor airplane which shared the same nickname. That revolutionary airplane was one of the first all-metal aircraft to be used in civilian transport and had a safety and reliability record that was second to none. So much so that it was dubbed "The Safest Airliner Around". A fitting nickname for Tucker's safety car with aircraft-inspired looks.

On March 4, 1947, the design firm of Lippincott and Margulies was hired on as consultants to provide some fresh ideas.

On March 11 the Lippincott team arrived at the Tucker plant, led by Hal Bergstrom and accompanied by additional designers Budd Steinhilber, Tucker Madawick, Read Viemeister and Phil Egan. Here's how Phil Egan described Alex Tremulis' plant tour and his reaction to seeing the "Tin Goose" for the first time:

“Here we saw embryonic shapes in raw sheet metal coalescing into the frame and part of the body of an automobile. A nearby drop hammer pounded sheet metal from flat to contoured with ear-splitting vibrations, and the junctions of formed sheet and frame were fused under the bright sparks of welding torches. Elsewhere, men at work stations devoted themselves to the mechanical details of torching, cutting, bending, and drilling the parts of a prototype automobile. Alex [Tremulis} gave us a cursory introduction to all of this and then led us to the design area.

Since he had accepted the position of chief stylist in January, Alex had brought the design of the Tucker automobile from the nebulous to the three-dimensional. He had developed a firm layout of the car which he showed us in a 1/8 size drawing, with every outside and inside dimension carefully indicated.” - Phil Egan, Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile, 1989

It was at this time as well that there would finally be enough clay available to build two full-size models, one for the current design and one for the soon-to-arrive Lippincott team. Tremulis had begun work on what would become known as Clay #1 shortly before the Lippincott team's arrival. As Phil Egan would attest: "A two-man crew worked on the beginnings of a full-size clay model of a car. We could discern a shape in that brownish clay which was clearly the essence of the Tucker '48 I had seen in the newspaper advertisement. I noticed that the details at front and rear were vague, without resolution".

Further refinement of the Tucker ’48 details were carried out with design input from both the Lippincott Team and Tremulis, the significant details of which will be discussed later, but for now, the Tucker ’48 was complete enough to identify it as a distinctly different car than the one described as the Tucker Torpedo.

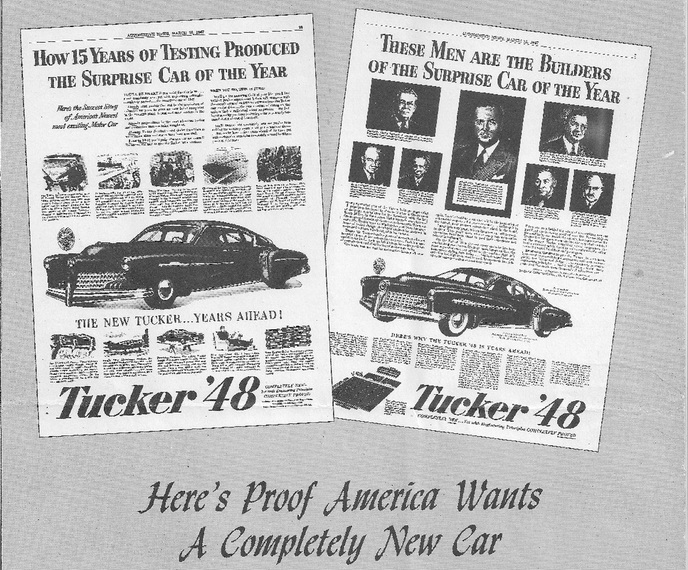

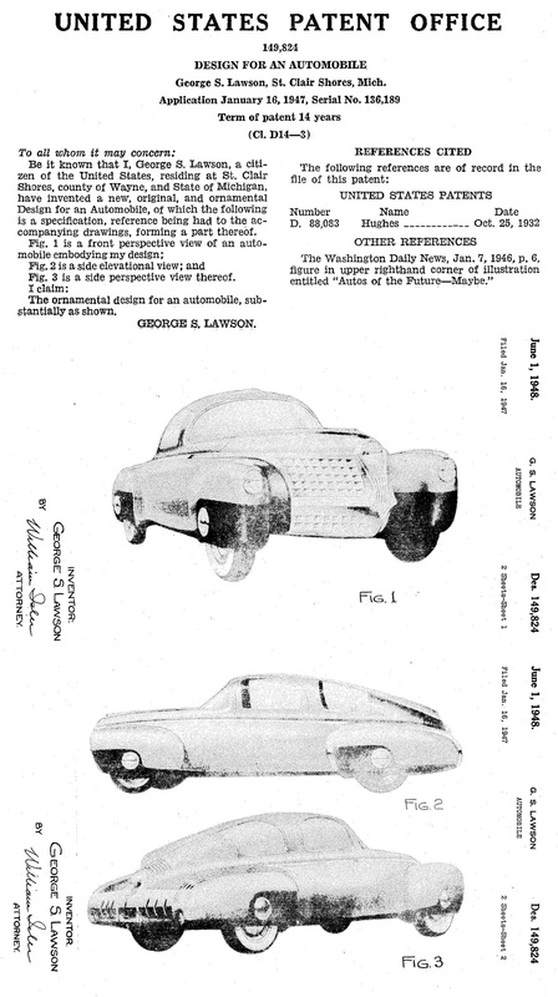

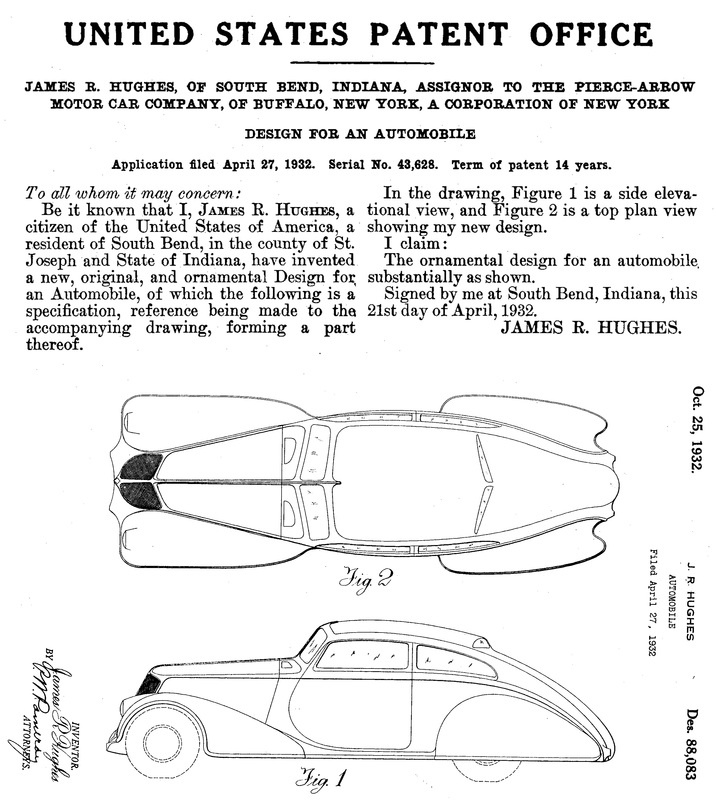

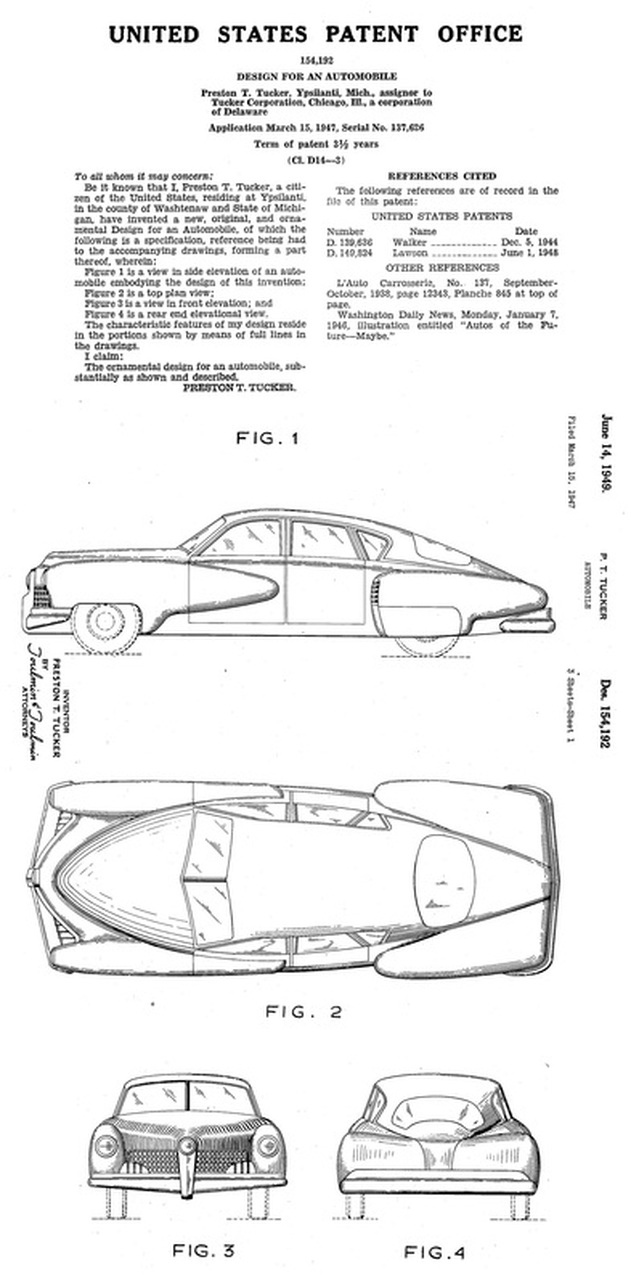

If there was any lingering doubt that these weren't two distinctly separate designs, one needs only to look at the intellectual property generated for the Tucker Torpedo and the Tucker '48. What transpired with the patent filings brings to light how the two designs were viewed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Special thanks to Hemmings Motor News/Special Interest Autos for their historical archives and images, and to Larry Clark, Tucker historian, for his tireless research and dedication to the Tucker automobile and all those that helped create it.

Some Tucker must-reads:

The Indomitable Tin Goose, Charles Pearson, 1960

Epitaph for The Tin Goose, Alex Tremulis, Automobile Quarterly, 1965

Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile, Phil Egan, 1989

RSS Feed

RSS Feed